Zoom is finally getting this huge upgrade — what you need to know [updated]

Zoom is getting end-to-end encryption, but it's not quite clear yet how to enable it

UPDATED throughout with comments and explanation from Zoom.

Zoom is finally letting meeting participants use end-to-end encryption in a trial run, after a couple of earlier announcements that implied such encryption would be available much earlier.

"Starting next week, Zoom's end-to-end encryption (E2EE) offering will be available as a technical preview, which means we're proactively soliciting feedback from users for the first 30 days," Zoom Head of Security Engineering Max Krohn said in a blog post yesterday (Oct. 14).

- Best free Zoom backgrounds

- Zoom privacy and security issues: Everything that's gone wrong

- Plus: Best Prime Day deals you can still get now

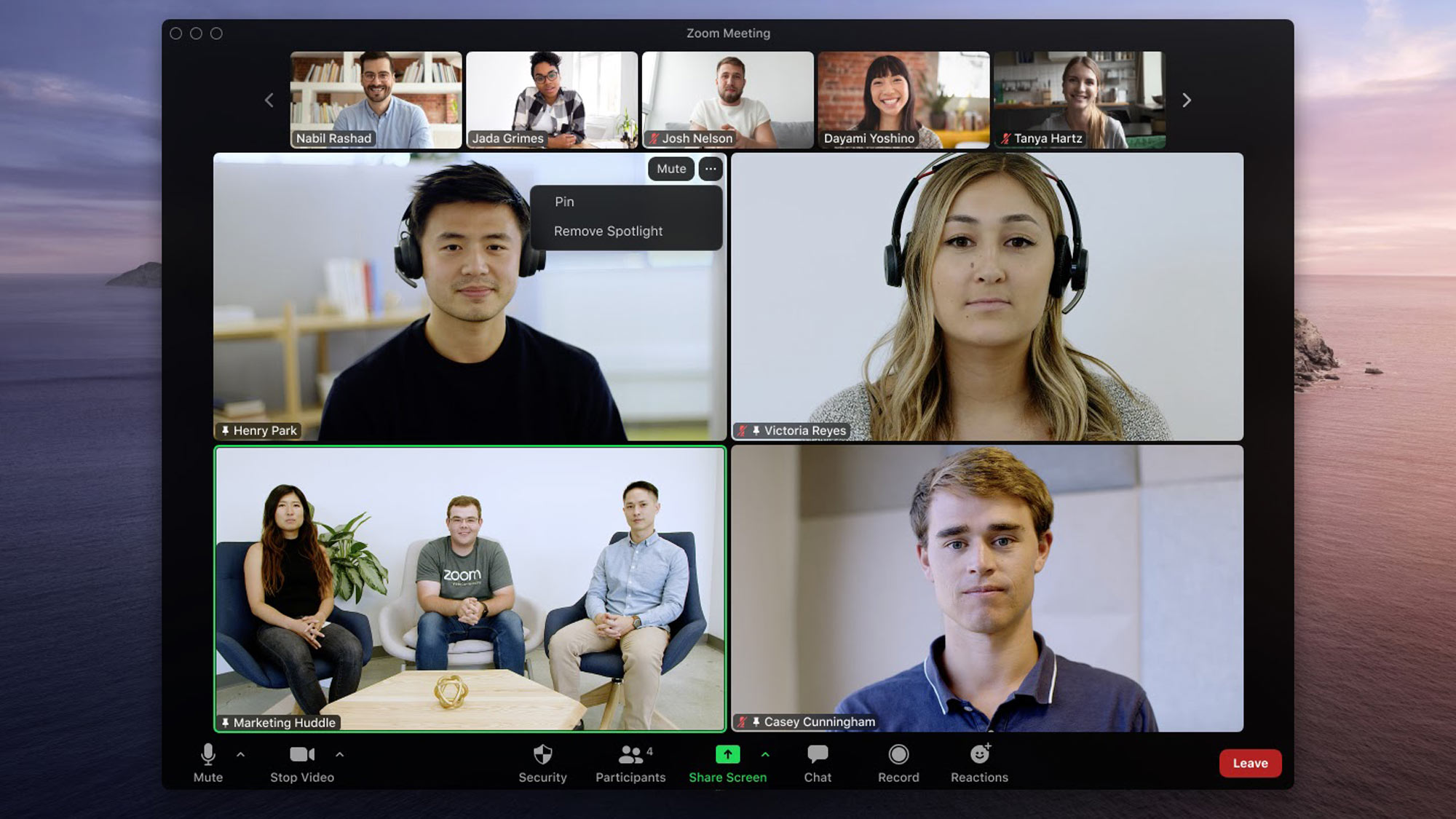

"Zoom users — free and paid — around the world can host up to 200 participants in an E2EE meeting on Zoom, providing increased privacy and security for your Zoom sessions."

This sounds lovely, but as with many things Zoom, the devil is in the details. First of all, it's not yet clear how to even enable this.

How do you turn on Zoom end-to-end encryption?

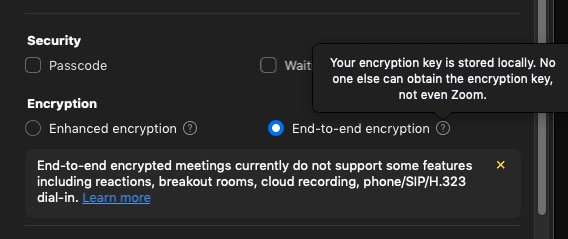

The Zoom "E2EE" will not be on by default, Krohn explains.

"Customers must enable E2EE meetings at the account level," he states, and the blog post includes a screenshot of what appears to be the settings screen of the Zoom desktop client.

Get instant access to breaking news, the hottest reviews, great deals and helpful tips.

We weren't able to find any such setting on own fully updated version of the Windows desktop Zoom client, and trying to adjust our profile settings bounced us to the Zoom website, which again came up empty.

"It will become available next week," a Zoom spokesperson said in response to Tom's Guide's questions. "It’s incredibly easy to enable in your web dashboard, and when scheduling meetings and participating in meetings."

Even after you enable E2EE, you will have to "opt-in to E2EE on a per-meeting basis" — and that's only if the meeting host enables it on their end.

That may be just as well, because as Krohn notes, "Enabling this version of Zoom's E2EE in your meetings disables certain features, including join-before-host, cloud recording, streaming, live transcription, Breakout Rooms, polling, 1:1 private chat, and meeting reactions."

He doesn't mention it, but we can't imagine that someone will allowed to join an E2EE meeting if they're calling in from a phone line. And joining from Zoom's web-browser interface, rather than from the Zoom desktop or mobile client software, might also be problematic.

The Zoom spokesperson confirmed both points.

"Zoom end-to-end encryption does not support dialing in by traditional phone line, or browser," the spokesperson told Tom's Guide. "It’s difficult to prove when a meeting is truly end-to-end encrypted through a browser, which is why we aren’t supporting that in phase 1."

"Individual Zoom users will want to weigh whether they need these options before enabling end-to-end encryption in their meetings," the spokesperson added.

How does Zoom's end-to-end encryption work?

To get more technical, it's strange that Krohn is using the acronym "E2EE" to refer to end-to-end encryption, when the rest of the computer industry uses the more commonplace "E2E."

This makes us wonder is Zoom is again fudging the definition of "end-to-end", as it did for years by claiming that data encrypted between the client and the server counted as "end-to-end."

It most certainly did not. End-to-end encryption is when only the two devices at either end of a communication can read the message. Intermediary parties — network servers, device makers, service providers — should not be able to.

"This is the real deal," the Zoom spokesperson told Tom's Guide, and referred us to a GitHub page that documents the progress of Zoom's encryption implementation. including a white paper from yesterday that Krohn co-authored along with some prominent encryption experts.

"We use 'E2E'to mean 'end to end,' and use 'E2EE' for 'end-to-end encryption' (three E’s)," the spokesperson added.

Under Zoom's previous "end-to-end" implementation, Zoom's servers could decipher all meetings, which meant Zoom itself had access to whatever was said in those meetings.

That's not a problem when it comes to birthday parties and school classes, but government and corporate clients might want to keep their data safe from a company that has extensive operations in China and was founded and is led by a Chinese national.

"Zoom is an American company, publicly traded on the NASDAQ, with a founder and CEO who is an American citizen, with headquarters in San Jose, California," the spokesperson noted.

To resolve that embarrassing situation, Zoom bought an encryption provider called Keybase in May, the results of which we see today.

Who's generating the encryption keys?

Krohn's blog post does not clear things up, because he uses two possibly contradictory explanations of how Zoom's "E2EE" will work.

"Zoom's E2EE offering uses public-key cryptography," he says in a FAQ. "In short, the [encryption] keys for each Zoom meeting are generated by participants' machines, not by Zoom's servers."

Right. That's the way end-to-end encryption is meant to work. So far, so good. (The public-key cryptography does not create the actual encryption key, but is a way to securely transmit that encryption key to the other participant.)

But earlier in the same post, Krohn states that "with Zoom's E2EE, the meeting's host generates encryption keys and uses public-key cryptography to distribute these keys to the other meeting participants."

That makes less sense. Who exactly is generating the encryption keys? The meeting host, or the other participants' machines?

"It's the host's machine," the Zoom spokesperson said in reply to our questions.

Exactly what kind of encryption keys are the meeting participants getting from the host? Are there individual encryption keys for communications between the meeting host and each individual participant, or do all meeting participants share the same encryption key? If hundreds of meeting participants share the same encryption key, then does it really count as end-to-end encryption?

"They all share the same meeting key, but they use different public/private key pairs to communicate that meeting key," the Zoom spokesperson told us after this story was first published.

Paul Wagenseil is a senior editor at Tom's Guide focused on security and privacy. He has also been a dishwasher, fry cook, long-haul driver, code monkey and video editor. He's been rooting around in the information-security space for more than 15 years at FoxNews.com, SecurityNewsDaily, TechNewsDaily and Tom's Guide, has presented talks at the ShmooCon, DerbyCon and BSides Las Vegas hacker conferences, shown up in random TV news spots and even moderated a panel discussion at the CEDIA home-technology conference. You can follow his rants on Twitter at @snd_wagenseil.

Club Benefits

Club Benefits