Sex, Ice Cream Dupe College Students Nationwide

Pretty ladies, job prospects and ice cream can get college students to click almost any link online, a recent study found.

Parties and sex may be highlights of a college experience, but they can also influence students into making terrible decisions online, a study conducted by a Johns Hopkins computer science class has found.

Working with two advisors from Baltimore security firm ZeroFOX, students in Professor Avi Rubin's computer-science class spent the fall semester of 2014 using social media to lure students at 16 other American colleges and universities to potentially malicious websites.

The students found that a fake Tinder profile of a pretty coed at Drexel University in Philadelphia got 75 percent of male students to click a possibly malicious link. Phony Facebook pages of hot women wearing yoga pants got 991 friend requests in two hours, plus a marriage proposal. And fake ice-cream discounts tied to a Syracuse football game became a trending topic on Twitter before the game was even over.

MORE: 10 Facebook Privacy and Security Settings to Lock Down

The project was an attempt to see how vulnerable college students, and the campus networks they use, are to social-media-based attacks, said ZeroFOX researchers Chris Cullison and Zack Allen in a presentation at the ShmooCon 2015 security conference in Washington, D.C., last month.

"This is their main form of communication. Interaction on social has surpassed email," Cullison said during the presentation. "A whole generation of college students may not even have an email address, but have five, 10 different social accounts."

Universities "have a really unique problem," Cullison said. They tend to be open by their very nature — yet still need to keep grades, research papers and other proprietary information private. But if students can be lured to sites that can install malware on their computers, he explained, then campus networks can be compromised and penetrated.

Get instant access to breaking news, the hottest reviews, great deals and helpful tips.

The team chose 16 schools around the country as targets for their social-media experiment: Columbia, Cornell, Drexel, Duke, Georgia Tech, the University of Miami (Florida), Michigan, Michigan State, UNC Chapel Hill, Penn, Penn State, the University of Rhode Island, USC, Syracuse, the University of Virginia and Virginia Tech.

"We wanted schools where there are active student bodies and active alumni bodies," Cullison told Tom's Guide. "We wanted to see if rival schools would cross-pollinate on social media — for example, Chapel Hill and Duke." (They did.)

Here's the hook, find bait

Students were to spend two weeks on a "red team" attacking a specific school, and two weeks on a "blue team" defending a different school against their classmates' attacks.

"Each team was given a unique link," Cullison said. "They could go ahead and shorten it, do whatever they needed to do with that link, but their goal was to get people to click it. So they would go out to social media and go ahead and post it out there in whatever way they felt [was necessary] to try to get the most clicks from that different university. We would then take those results and see who clicked."

Each link led to what appeared to be a 404 page, a "page not found." But embedded in each page was an image, sometimes a smiley face, that hid a script that logged the type of browser and Internet Protocol address being used by the visitor.

"If we wanted to do something malicious, and we were the bad guy and we wanted to run bad script, [then] they've bit the hook," Cullison said. "We have them. If we were bad, this is how successful something like this could be."

Love and money

The methods of attack leveraging social media were mostly left up to the students. Yet Cullison and Allen were impressed with what the undergraduates devised.

One team attacked the University of Michigan by creating a bogus job site that solicited resumes. It got 972 visits, with a 12.5 percent resume-submission rate. In order for the site to work properly, the team had to pretend to be an insider — so one of its members contacted the alumni office, said he was an alumnus who'd lost his original University of Michigan email address, and was assigned a new one.

"From there, they were then given access to all of the closed University of Michigan pages out on Facebook," Cullison said, adding that the team then put the word out on Facebook asking for names and resumes.

"It was extremely successful," Cullison said. "This link was actually re-sent out by other people within Michigan. ... Even until the student finally shut down this email address, he was still getting emails over and over after he had shut down the site, because people were still trying to go out, find jobs and click on it."

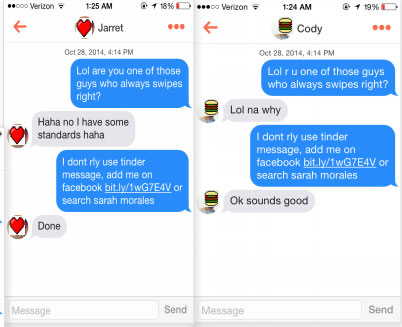

Another student first tried to attack Drexel by creating a fake Twitter comedian based in Philadelphia. That didn't work well. So he asked a friend if he could borrow some of her pictures and used them to create a fake Tinder profile of a pretty girl named Sarah Morales. Interested male students chatted on Tinder with "Sarah," who was really a chat bot — an interactive program that issues preprogrammed responses.

"LOL r u one of those guys who always swipes right?" the Sarah-bot asked. Twenty minutes later, the bot added, "I dont rly use Tinder message, add me on Facebook bit.ly/1wG7E4V or search Sarah Morales."

Seventy-five percent of the men who chatted with the bot clicked the link, which went nowhere. But it could have just as easily led to a malicious page that dropped malware on their phones.

MORE: Soulmate or Cybercriminal? How to Avoid Online Dating Scammers

Ice cream and sex

One team tried to clone organizational Facebook accounts, which should be impossible because Facebook won't let anyone else create new pages for, say, Starbucks.

But the team replaced letters in names with similar-looking characters from other alphabets — for example, by substituting the "c" in "Starbucks" with the Cyrillic letter for "s," which looks like "c" — to create a fake Starbucks page. The team then went further by Photoshopping Facebook's "verified" checkmark from the real University of Miami page to the team's own fake page.

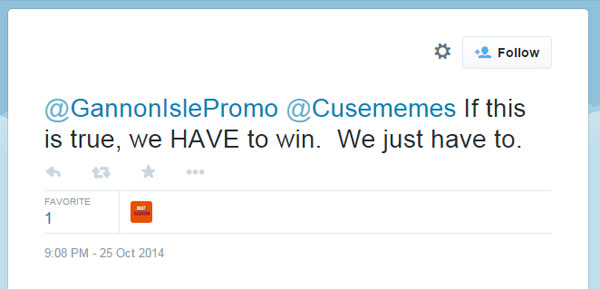

Twitter proved harder to spoof, since the service scans for duplicate feeds. But it was vulnerable to well-timed attacks. During a Syracuse football game in October, one team used several fake Twitter accounts to start a rumor that Gannon's Ice Cream, popular with students, would offer discounts if the Syracuse Orange won — and included a shortened link, which promised details but actually only logged clicks.

"Students see this, they're watching the game," Cullison said. "They start sharing it, retweeting it, pushing it around. The student union picks up on it, various places pick up. They start retweeting it, this starts becoming one of their favorites, it starts getting huge."

One student even tweeted: "If this is true, we HAVE to win. We just have to." (The Syracuse team lost to Clemson 6-16.)

You have to do more than "just pull down a trending hashtag and post to it and get people to click," Allen said. "You really need to create something and create a post that people will relate to, like a deal or some awesome quote that somebody said to get everybody rallied up — it's all about timing."

The biggest success was by a student who used Google image results for "cute girl" to set up Facebook accounts for phony groups of sexy yoga-pants wearers at various universities — and used the Twitter hashtag "#yogapants" to direct followers to the pages. Each Facebook page had a link inviting visitors to check out "My Awesome Life" — a one-page external website that promised images of drunk women at wild parties, but which, of course, did nothing but log visitors.

"Within the first couple of hours, he had 991 friend requests, and, as it continued, up to 2,500 friend requests in a very short period of time ... including a marriage proposal," Cullison said. "At some point, Facebook said, 'Hey, you need to verify you are you. You're way too popular.'"

The "lovely young ladies" even snared other students in the Johns Hopkins class, who didn't realize until the end of the semester that they'd been duped by one of their own classmates.

"You should have seen some of their faces at the final presentation as they went, 'Oh my God, I friended that," Allen said.

Lessons learned

Allen and Cullison didn’t have much to say about the methods the students used to defend against social-media attacks, other than to point out that once a malicious URL is shortened by a given shortening service, it never changes and hence will be easy to detect. They also said that Facebook, Tinder, Twitter and other social-media services the students used were alerted to the successful attack methods, even if the targeted schools weren't tipped off beforehand.

Cullison stressed that while these social-media pranks may have been benign, similar attacks in the future may not be.

"In a real-world example, look at what just happened with ISIS and Centcom," Cullison told Tom's Guide, referring to a recent incident in which the Pentagon's Central Command Twitter feed was briefly hijacked by someone claiming to represent ISIS, or the Islamic State. "They had the keys to drive. Let's say they wanted to use that account to spread malicious things. They had all that ability.

"Attackers are using these methods to launch very large and very malicious attacks," he added. "This study was a way to illustrate how students were able to replicate this."

- 7 Scariest Security Threats Headed Your Way

- Lenovo's Security-Killing Adware: How to Get Rid of It

- 9 Online Security Tips from a Former Scotland Yard Detective

Paul Wagenseil is a senior editor at Tom's Guide focused on security and gaming. Follow him at @snd_wagenseil. Follow Tom's Guide at @tomsguide, on Facebook and on Google+.

Paul Wagenseil is a senior editor at Tom's Guide focused on security and privacy. He has also been a dishwasher, fry cook, long-haul driver, code monkey and video editor. He's been rooting around in the information-security space for more than 15 years at FoxNews.com, SecurityNewsDaily, TechNewsDaily and Tom's Guide, has presented talks at the ShmooCon, DerbyCon and BSides Las Vegas hacker conferences, shown up in random TV news spots and even moderated a panel discussion at the CEDIA home-technology conference. You can follow his rants on Twitter at @snd_wagenseil.

Club Benefits

Club Benefits