'Don't Take Nude Selfies' Is Not Good Security Advice (Op-Ed)

Don't say, 'She shouldn't have taken them.' The people who stole and leaked actresses' nude photos are the ones at fault.

Here at Tom’s Guide our expert editors are committed to bringing you the best news, reviews and guides to help you stay informed and ahead of the curve!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Tom's Guide Daily

Sign up to get the latest updates on all of your favorite content! From cutting-edge tech news and the hottest streaming buzz to unbeatable deals on the best products and in-depth reviews, we’ve got you covered.

Weekly on Thursday

Tom's AI Guide

Be AI savvy with your weekly newsletter summing up all the biggest AI news you need to know. Plus, analysis from our AI editor and tips on how to use the latest AI tools!

Weekly on Friday

Tom's iGuide

Unlock the vast world of Apple news straight to your inbox. With coverage on everything from exciting product launches to essential software updates, this is your go-to source for the latest updates on all the best Apple content.

Weekly on Monday

Tom's Streaming Guide

Our weekly newsletter is expertly crafted to immerse you in the world of streaming. Stay updated on the latest releases and our top recommendations across your favorite streaming platforms.

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Your email account got hacked, and all your messages were posted online. It's your fault for not using a better password. Your World of Warcraft account got hijacked, and someone stole all your gold. It's your fault for playing video games. Your credit-card data was stolen. It's your fault for having a credit card.

Your photo-storage service or smartphone was hacked, and someone posted your nude selfies online. It's your fault for taking photos that other people find desirable.

MORE: How to Prevent Your Nude Photos from Going Online

Most people would find the first three assertions ridiculous. Using a guessable password, playing an online game or having a credit card may be inherently risky propositions, given the nature of the Internet, but they don't mean you're at fault when someone else hacks your account.

But when the stolen data consist of selfies privately taken by famous women posing nude, suddenly people leap to blame the victims of the data breach, not the perpetrators.

Virtually no other type of breach provokes this kind of blame-the-victim response. "She shouldn't have done it" isn't actually sound technological advice. It's moralizing, condescending and puritanical.

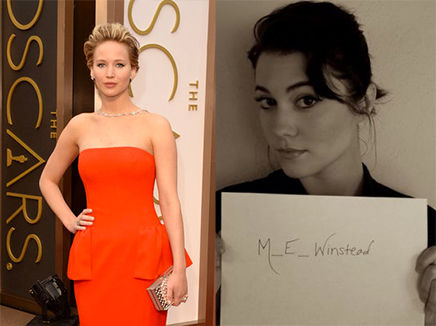

Jennifer Lawrence, Kate Upton, Kirsten Dunst and the other actresses whose nude photos appeared on Internet forums Reddit and 4chan this weekend are not at fault for these data leaks. The only people responsible are the ones who stole, collected and apparently trafficked these photos for years before the spoils of their thefts appeared online.

Get instant access to breaking news, the hottest reviews, great deals and helpful tips.

"Don't take nude selfies" is not only victim blaming, it's simply not viable. Taking nude selfies may not be "necessary" in the way that having an email address or a credit card are, but neither is playing an online game, and no one would describe playing World of Warcraft as "scandalous" or tell players they "shouldn't have done it."

Encouragingly, the conversation surrounding this round of female celebrity nude photo leaks is less accusatory than in previous leaks. In 2007, when a nude photo of Disney Channel star Vanessa Hudgens appeared online, hardly anyone asked who had actually leaked the photo, or questioned the security of the digital service used to store and transmit it. Hudgens, who was 18 at the time, was forced to apologize for a nude photo that someone else leaked without her permission.

"We hope she's learned a valuable lesson," said a Disney Channel representative of the incident.

This time, the question of who stole dozens of nude photos, and how they did it, is at the forefront of the conversation. Many experts and commentators have attempted to focus blame on the people who stole and exploited the photos, not the people who took them. Celebrity blogger Perez Hilton, who initially posted the photos on his website, quickly took them down and apologized for posting them in the first place.

That's not to say Jennifer Lawrence, Kate Upton and the more than 100 affected actresses haven't been shamed and blamed for the hacks. Under a Twitter hashtag #ifIwerehacked, people have boasted that they're "smart enough" or "responsible enough" not to take nude selfies, and that the only photos on their phones were of pets or of food. At best, this hashtag misses the point; at worst, it contributes to a culture of victim blaming and exploitation.

Could Jennifer Lawrence and the other women affected in the data breach have done more to protect their photos? Sure. "Security is a process, not a product," as security guru Bruce Schneier wrote in his book "Applied Cryptography" (Wiley, 1996).

Security experts could and probably should recommend that anyone, no matter what gender you are or how famous you are, use encrypted cloud storage services, secure messaging apps and complicated unique passwords.

But before offering that advice, people need to first acknowledge that a person's private data is that person's private data, and that "don't take nude selfies" is neither good advice nor appropriate commentary.

The fact is, the theft of these women's nude photos was a theft. It was an invasion of privacy. It was the digital equivalent of robbing a bank and stealing money from accounts held in the bank. Just because the "safe" the criminals broke into to steal these private photos wasn't as strong as it "could have been," or even because the photos existed in the first place, does not make the theft any less of a crime or an outrage.

- 12 Computer-Security Mistakes You're Probably Making

- Best Free PC Antivirus Software 2014

- 7 Scariest Security Threats Headed Your Way

Jill Scharr is a staff writer for Tom's Guide, where she regularly covers security, 3D printing and video games. You can follow Jill on Twitter @JillScharr and on Google+. Follow us @tomsguide, on Facebook and on Google+.

Jill Scharr is a creative writer and narrative designer in the videogame industry. She's currently Project Lead Writer at the games studio Harebrained Schemes, and has also worked at Bungie. Prior to that she worked as a Staff Writer for Tom's Guide, covering video games, online security, 3D printing and tech innovation among many subjects.

-

DarkSable I came here to post a rebuttal arguing that while it's poorly phrased, the advice is sensible when it boils down to: "Don't put something you don't want found where it could be easily found." It's a concept of physical security and digital security; if it's stored on the cloud, you're trusting someone else's security, not just your own.Reply

That being said, this article wasn't arguing the points I thought it was going to, and makes perfectly valid points. Surprisingly strong, well-argued content for Tom's Hardware; keep it up, Jill. -

Christopher1 Thank the author for writing an article like this. The 'shaming' of a woman who did what numerous people do is sickening to me, it sounds like a bunch of Puritanical BS like we had during the 1700's from the actual Puritans.Reply -

skit75 I'm not trying to blame the victim here, either, but you know you did backup or store your data online or in the cloud. From what I hear and have read, it looks to be more of a targeted attack against the user accounts themselves. Still, the data would still be theirs if they had chosen a safety deposit box or even a shoe box in the closet. Nothing online is private, or secure.Reply -

CaedenV Do whatever you want, but if it is stored on the internet or goes through a network then just know that there is a very real chance that SOMEBODY will be looking, and if that something is particularly interesting then SOMEBODY will share it to the greater public. Not saying it is right, because it certainly isn't, but it is a fact of life that everyone has to deal with on one level or another. If you are going to do something meant to be private then store it on private local machines, and distribute it over private media (CDs, flash drives, SD cards, whatever).Reply

These are things that nerds have had to deal with for 20+ years now, and if the general public is going to play on our turf, then they get to inherit the concerns of nerds too. -

bwcbwc I'll write off the phrase "moralizing, condescending and puritanical" as authorial hyperbole to make the point hit home. I can certainly agree that a lot of the reaction to this "scandal" is a) emblematic of our ongoing societal double-standard when it comes to sexuality expressed by men and women and b) symptomatic of the misogyny in the tech community. But maybe we should take "she shouldn't have done that" as a technical recommendation rather than a moral one - in other words, if you don't want to risk it being hacked, don't connect it to the internet in any way, shape or form. Obviously we're looking at some statements from completely different points of view - such a technical recommendation can easily be interpreted as "blaming the victim". But we don't leave our homes unlocked anymore and our cars have several layers of locks instead of open sides and an ignition button. From my POV, unless "she shouldn't have done that" is actually followed by a "moral" argument against public nudity, it's more 20/20 hindsight about security precautions than blaming the victim. Which, in retrospect, is still pretty condescending. So I'll give on that one.Reply -

maban I really didn't care to read the rest of the article as opinion pieces are generally bullshit. But I would like to disagree on the notion that using a weak password is not the user's fault. While that user isn't actively instigating a "hack" they are not protecting themselves in a manner that anyone would consider proper. The official Apple release says that the "hack" was due to a "very targeted attack on user names, passwords and security questions." In other words, it was partially the user's fault for using a guessable password/security questions. I would like to use the analogy of leaving your car unlocked and it being stolen but it's more like permanently parking it in a crime-ridden part of town.Reply -

fkr or you can setup accounts so that when a non trusted computer logs into your account it must have a onetime password entered that is sent to the account owner by sms. this is an old story about a fool and his moneyReply

I feel for those who get hacked and such but really if you make millions of dollars but you do not have the common sense to hire somebody to help you with your sensitive information you only have yourself to blame. -

Necr0v The first section in this article "It's your fault for not using a better password" and "Most people would find the first three assertions ridiculous.".Reply

Is it ridiculous to say that if I picked using qwerty or password as a password then it's not my fault? That I shouldn't have my emails hacked because it's up to me to choose my own password and that's a fundamental right of mine?

I'm pretty sure in the last 6 months I have read more articles on here than I can count about using strong passwords and perhaps 2-step verification for accounts that matter (which I would assume includes email).

Not arguing that it's ok for people to hack others email accounts, but if you leave yourself so blindingly open to such things what do you expect?

-

drapacioli Look, I'm not saying a victim is to blame for this sort of stuff, but what I am saying is that cloud security is NOT up to par. Yes, the people that stole it (yes, STOLE, not leaked!) have committed the crime and the celebs are not to blame for these, but there are steps people can take to avoid this situation entirely. Is it your fault that you might not know that your data isn't secure? Well, no you can't be faulted for it, especially if the company hosting your cloud content touts their security as a main feature. The big problem is that even today's best security is being rapidly overwhelmed by hackers and thieves. Remember all the credit card fraud articles from at least 2 dozen retailers this year? Yeah, you're not at fault for shopping there either, but the people/company in charge of making sure those transactions are secure aren't doing everything they can to stop these. Why are we still using encryption that can be cracked on the fly with modern technology? Why are card readers and registers still running on windows xp? These aren't secure at all, and neither is cloud storage if the people in charge are using outdated security protocols.Reply

So yes, the criminals need to be caught, but the companies also need to be more proactive in making sure their services and systems are secure. I'm annoyed at the people that have the nerve to steal such private information and then distribute it, but I'm even more ticked off that companies just don't seem to care enough to spend any real money on fixing the underlying problems with their security. THAT is what I take from all that has happened recently. Also, the internet is still immature, but maybe it's getting slightly better? -

drapacioli Also I would like to point out that having a bad password is not a good idea regardless of whether or not the theft is "your fault," because it just enables others. If your password is 16+ characters with numbers and symbols and it's still cracked, there was nothing you could do. But if your password to your intimate photos was "password" well you kind of did leave that wide open. It's like writing down the safe combination and putting it on the fridge for a burglar to read if they decided to break in. You are still the "victim" but you aren't exactly helping yourself either...Reply

Club Benefits

Club Benefits