How to Make and Store Archival Prints of Your Photographs

You can create family heirlooms out of your photographs. It's pricey, but can be worth the cost. Follow our instructions about paper and ink.

Here at Tom’s Guide our expert editors are committed to bringing you the best news, reviews and guides to help you stay informed and ahead of the curve!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Tom's Guide Daily

Sign up to get the latest updates on all of your favorite content! From cutting-edge tech news and the hottest streaming buzz to unbeatable deals on the best products and in-depth reviews, we’ve got you covered.

Weekly on Thursday

Tom's AI Guide

Be AI savvy with your weekly newsletter summing up all the biggest AI news you need to know. Plus, analysis from our AI editor and tips on how to use the latest AI tools!

Weekly on Friday

Tom's iGuide

Unlock the vast world of Apple news straight to your inbox. With coverage on everything from exciting product launches to essential software updates, this is your go-to source for the latest updates on all the best Apple content.

Weekly on Monday

Tom's Streaming Guide

Our weekly newsletter is expertly crafted to immerse you in the world of streaming. Stay updated on the latest releases and our top recommendations across your favorite streaming platforms.

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

How Photos Disappear

Do you remember your parents or grandparents bringing out an old shoebox filled with all the family's photographs? Dozens and dozens of pictures, many dog-eared, creased, or torn? One corner missing? And, did you ever see the negatives in the same box with the prints? What happened to all those negatives?

Truth be told, if your family is anything like mine, the negatives ended up in a landfill decades ago. No one seemed to consider that the negatives could always create another copy of that old family picture, so they didn’t bother to keep it around.

Of course, there is one other problem that those old pictures present: If they are color prints, the colors will have noticeably started to fade and shift from their original vibrancy, even if they were shot as recently as 15 to 20 years ago. However, black-and-white pictures always seemed to last longer.

But, with today's digital images, we don't need to worry about losing the negatives. We only have to copy our pictures onto a DVD or CD or store them on a photo-sharing or social networking site. Never mind that those DVDs will likely last no longer than 10 years or that a storage service could have a catastrophic loss of capacity or go out of business. Many of us also thought we were being clever and made sure to print out the images we wanted to keep readily at hand.

Related: Best Cloud Backup Services

You won't be terribly surprised to learn that the prints made from your $79 printer will probably last for less time than the color prints made back in the 1970s. So, now you have a problem. How do you protect not only your digital files, but also safeguard your family's digital history? How do you, in fact, make long-lasting photographic history? This article will show you.

Preserving Your Family History

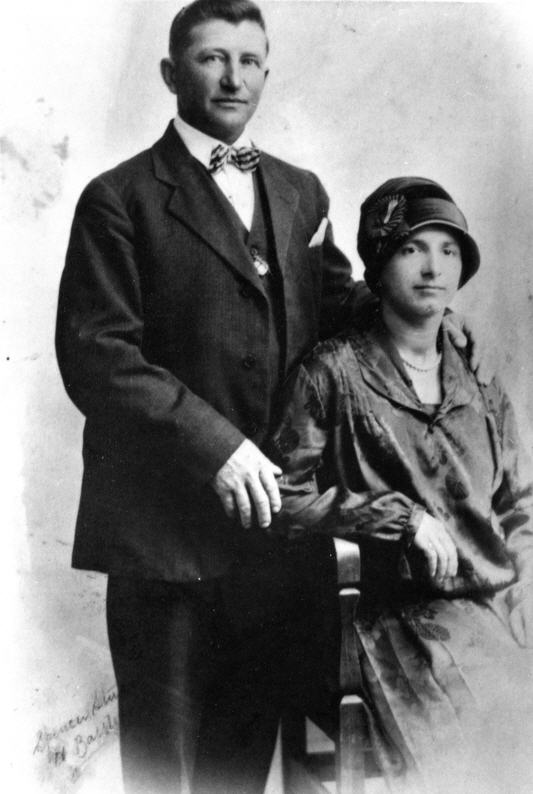

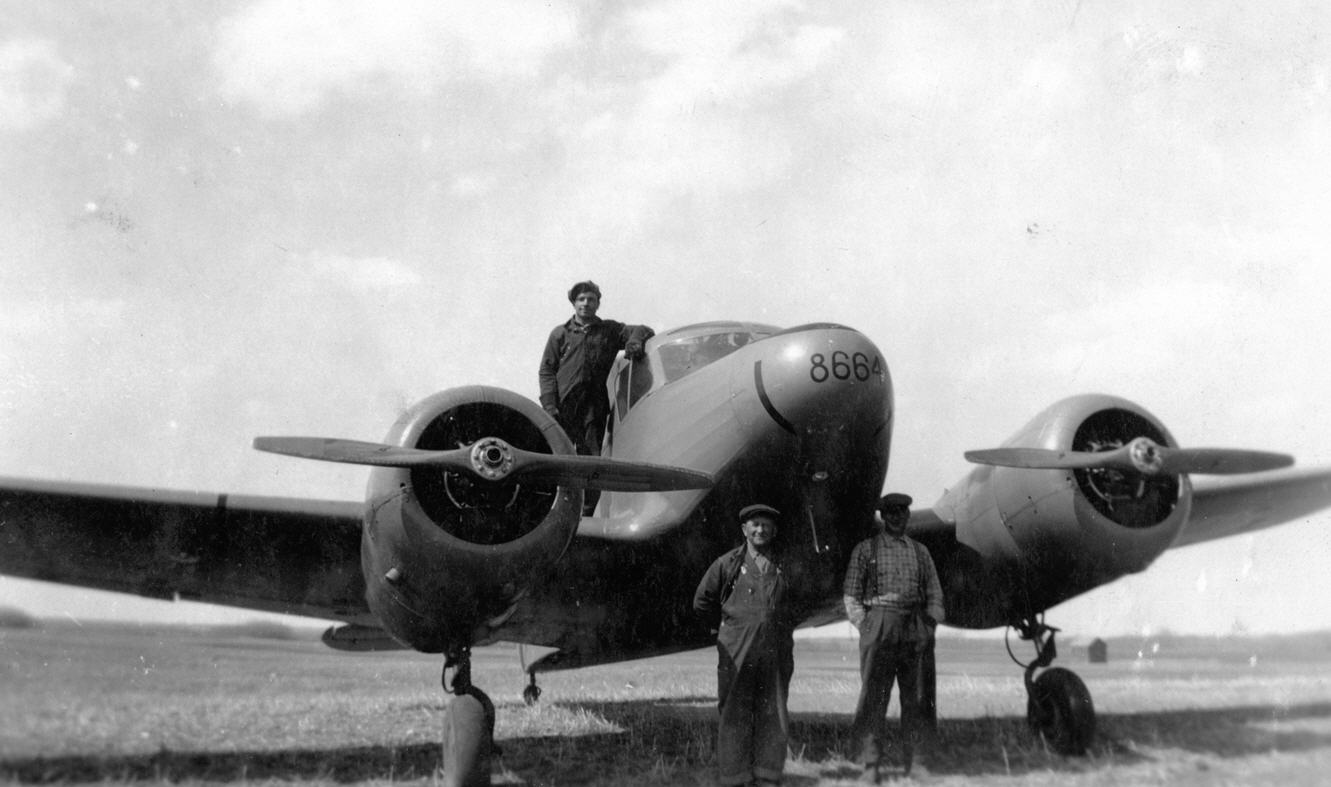

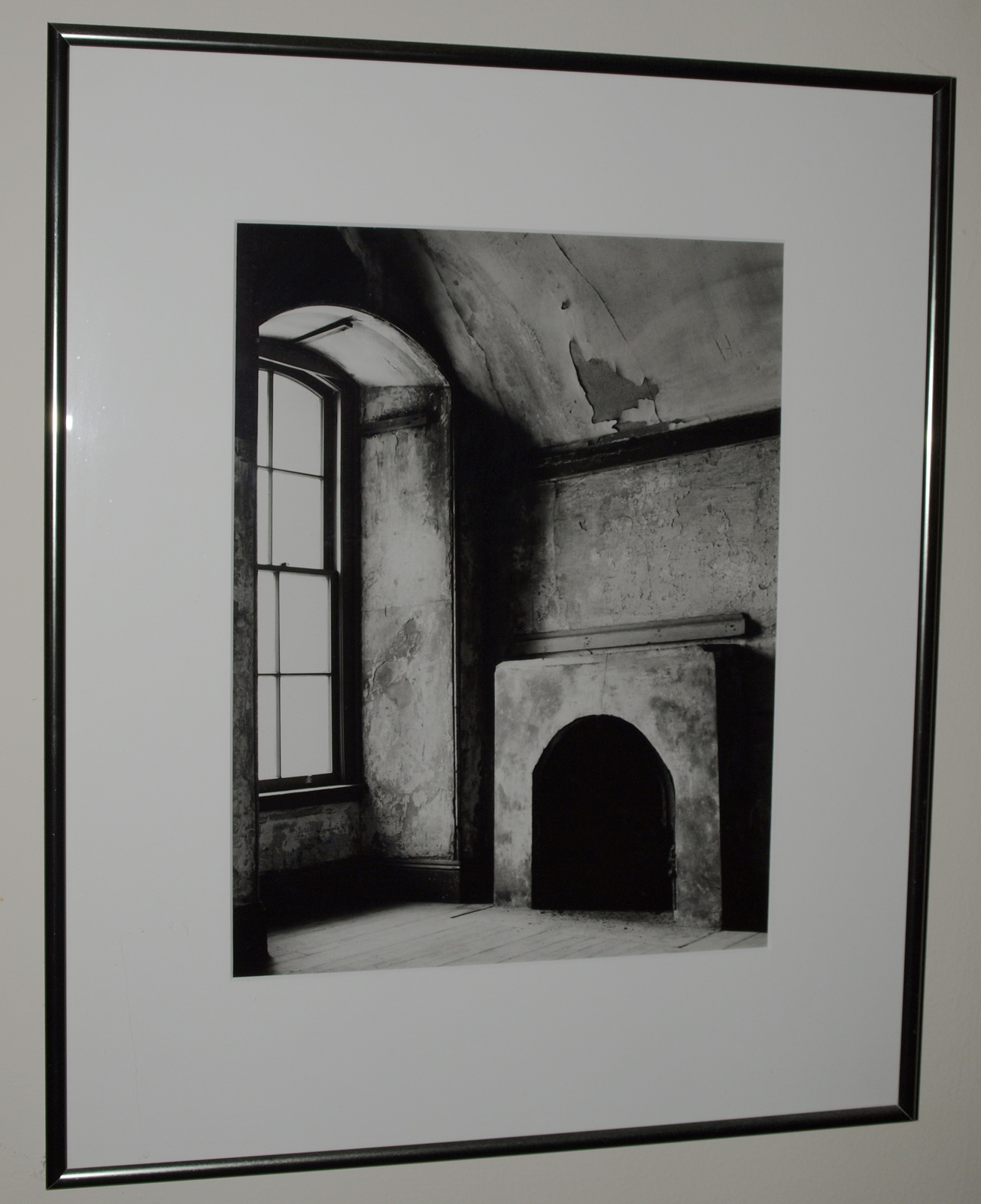

Why should you bother with a little extra effort to create a digital print that will last for more than a few years? Because by taking the time and making that extra effort you will have historical treasures of great importance to your family, just as you see in the photos on these pages. This first image here is a picture of my grandfather working his land in the early 1920s, a team of four horses hitched to his farm implement. Or, in the next photo, again from the 1920s, a picture of my mother and my uncle playing on the family car. The materials used at that time have proved to be of such durable longevity that my family can now look back and remember proudly who our family was and what we did.

Get instant access to breaking news, the hottest reviews, great deals and helpful tips.

These pictures exist today only because the materials used have certain archival properties that the majority of photographic prints made today lack. By archival quality, I mean that a picture (primarily black-and-white pictures from that era) was printed on photographic paper that used silver for its light-sensitive emulsion and paper that was relatively acid-free. Most color photographic materials today use organic dyes for their color images and papers that have a higher acidic content than the papers from decades ago did.

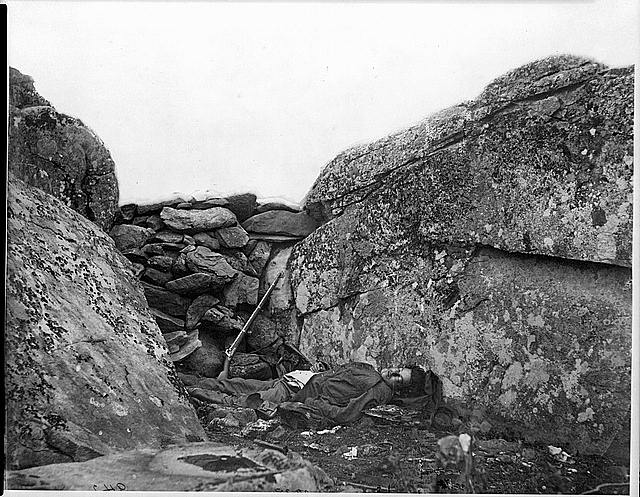

A Short History of Archival Prints

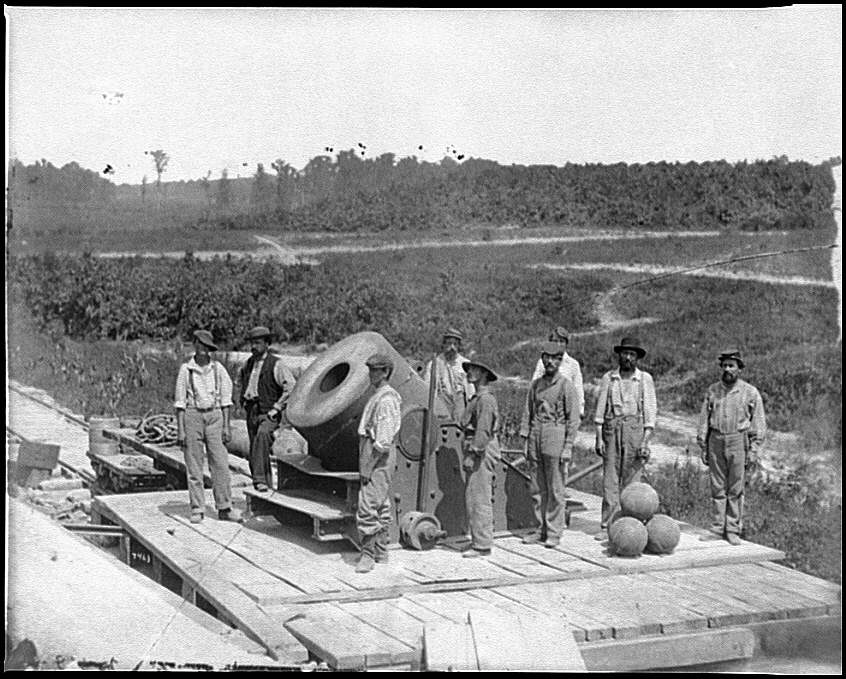

The American Civil War was one of the first conflicts that had the photographic coverage we have come to expect with our daily news today. We have a better sense of the carnage because photographs from that era make the history real. Our history books have shown this picture "Dead Confederate soldier in Devil's Den," credited to Matthew Brady, taken shortly at the end of the Battle for Gettysburg. This image as well as hundreds of others, such as "The "Dictator" shown here that was taken in Petersburg, VA, exist today because the photographers that created them used materials that would stand the test of time. that is materials that were of archival quality.

Their negatives were made from glass plates. These plates were coated with a light-sensitive material, most frequently as part of what is called a "wet-plate" process. The plate was taken into a tent, the light-sensitive solution was applied, and the photographer then ran out to expose that plate. As often as not, the photographer then had to process the plate before the solution dried. (See here for a description of wet plate/collodion photography.) Bear in mind that the prints made during this time were the most important, since the glass plates were expensive and the photographer would clean off the negative image and reuse the plate.

The photographic prints made from these glass plates were printed on paper that was very low in acidic content. The papermaking process has, for many years, left an acidic trace in the paper that is the seeds of its own destruction. Over time, that acid will start to discolor and degrade the paper and the image. Papers from the Civil War era lack that same level of acidic content, thus minimizing their deterioration and preserving them for posterity and our history.

Which Type of Printer?

Inkjet printers have been outputting our images for several years. Inkjets cover just about every price point the photographer needs. But not all inkjet printers are created equal. While small, portable inkjet printers or multi-function printers can output your photo, are they really best suited for your purposes of adding your images to the annals of history?

Your printer has to be able to create depth and image quality within your archival inkjet print. And a printer that has only four or five inks in its ink set will not be able to do the image justice. Look for a photo-quality printer that has at least six, if not eight or more inks. These additional inks will complement the primary inks in such a way that varying the dot size or spacing cannot do with a printer that has fewer inks.

These photo-quality printers are still considered inkjet printers. They can be found at most consumer electronic stores, including Best Buy. Even though we will discuss using higher-end paper for long-lasting photographic prints, these printers can also print on regular bond paper and print text.

Color inkjet printers make use of four primary colors, cyan (C), magenta (M), yellow (Y), and black (K), also called the subtractive primaries. To these, a photo inkjet printer may add light cyan, light magenta, a photo black and a photo gray. Some printers also include a UV-coating cartridge to provide an additional protection to the print.

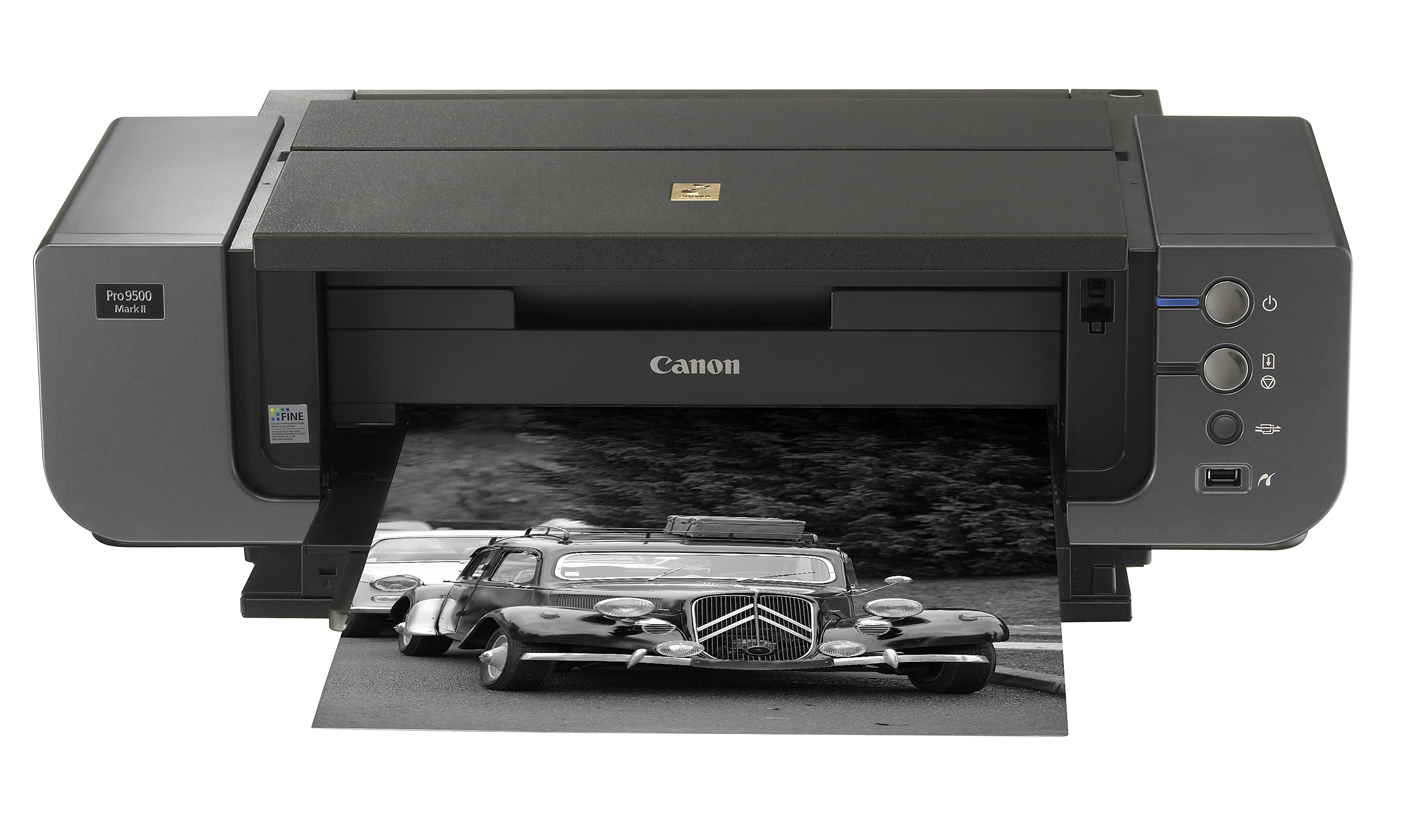

The additional colors let the printer fill in the nuances of shading and help create the depth you want for your historic print. These photo printers generate very small droplet sizes of three picoliters for the Epson Stylus Photo R2880, for example. This Epson model, along with the Canon PIXMA Pro 9500 Mark II, which we used for our tests for this article, can generate a Super B-sized print (13" X 19").

Related: Best All-in-One Printers

Dye-Based Inks

When inkjet printers first came to market, they used nothing but dye-based ink sets. These inks generated their color by making use of organic dyes. Those first prints might have lasted 18 months to two years at best before fading into oblivion.

The problem with the dye-based inks then was the lack of stability in the dyes. Since the dyes were organic in creation, they started to degrade as soon as they were shipped, much like the vast majority of color film. And this is the perfect analogy–since the organic dyes in film degrade with time, like a built-in shelf life, they cannot be expected to last forever. Remember those faded color prints from your grandparents' shoebox we mentioned earlier? That degradation of dye-based inks for inkjet printers also cannot be avoided. This first image shows an old color print and how the color of the sky and the mountains in the background have faded and shifted.

The second image is that of an inkjet-generated print, printed out about 15 years ago. Again, the blues of the sky and any sense of green have gone by the wayside.

Pigmented Inks

Any visit to a museum has introduced you to numbers of paintings created over hundreds of years. Many of those same paintings were done in oils, an artistic medium that has proved itself for its longevity and archival properties. One of the components in many oil paints is natural pigments. These natural pigments can be as elemental as a rock ground so fine as to remain suspended in the oil base of the paint. The pigments can also originate from the carapace of a bug, the ink from a cuttlefish, or natural colorants from plants, such as indigo.

There are benefits to using pigmented inks, other than the longevity factor. Pigments inks tend to sit on the surface of the paper (substrate) and they tend to resist washing out from the surface of that substrate. This surface placement lends itself to a printer using less ink to create the image, whereas the dye-based inks will likely seep further into the fabric of the paper. Because you can vary the particle size in pigmented inks, you can adjust the inks hue and saturation, thus altering how the color of the ink appears to you.

Pigmented inks are water resistant, unlike dye-based inks. In other words, a picture printed with dye-based inks can suffer from a drop of water dripping across the surface. The ink can re-dissolve and start to flow once again. This is not a problem with pigmented inks.

A few notes on buying a printer that uses pigmented inks: Yes, these printers are more costly than their dye-based ink counterparts. For example, the Epson Stylus Photo R1900 sells for about $550. That company’s R2880 costs about $650. The line of pigmented inks—called Epson UltraChrome—costs about $13 per color (and the R2880 needs eight different cartridges). So, the costs do add up. Another popular model is Canon’s Pixma Pro9500 Mark II, which uses Canon’s pigmented inks. Unfortunately, there is no third-party pigmented ink vendor that creates cheaper cartridges for your brand-name printer. That market exists for dye-based ink, but not pigmented ink, so you’re stuck using the pricey name brand.

Photographic Paper Back in the Day

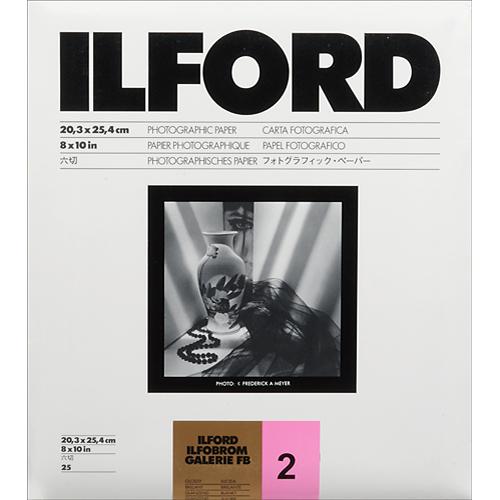

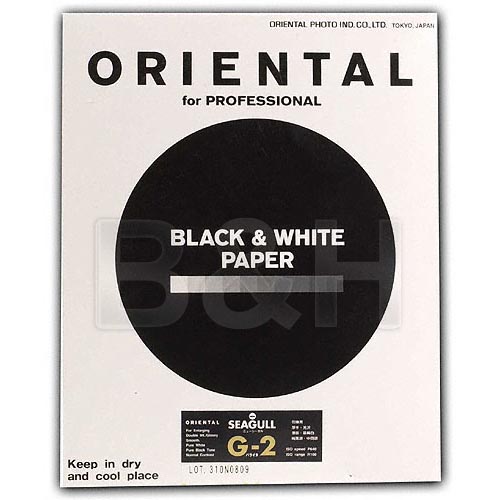

As we have previously mentioned, the photographs we associate with our history and the period of the dominance of analog photography had proper photographic papers and were correctly exposed and processed to ensure their archival quality and longevity. For the most part, these archival images have been printed on fibre-based papers.

Whether from Ilford or Oriental (two popular companies), or any number of other paper vendors, these papers need to be prepared properly to last for the ages. The typical darkroom experience used to include selecting the right paper for the image. The negative was inserted into the enlarger and composed on the easel, then a sheet of paper was placed in the easel with the lamp turned on, exposing the paper to the light.

Having thus created a latent image, you would process the paper through several chemical baths. These chemical baths would add acid to the paper, the mortal enemy for an archival print. The only way to eliminate that acid was with a thorough washing, preferably in an archival print washer. This bath could last up to two or three hours. After the wash cycle, you have to let the print dry out before you can take on any of the post-production steps to present a picture for archival purposes. But that was then. This is now. Read on to find out what we use instead.

Photo Gloss vs. Acid Free Papers

Photo Gloss Papers

The papers best used with the dye-based inks found in inkjet printers are much improved over what the photographer had to select from just 10 years ago. The current papers, along with the current dye-based inks, have much improved display life spans. Images printed today on these papers and dye-based inks will likely last well over 20 years, with some claims of over 30. The only problem with these claims is the fact that we will likely have no recourse in 20 to 30 years if the claims prove to be erroneous.

The expected life span of these images is no worse than what we can expect from a print made with a photographic process at your local drug or photo store. But, if your point is to create a print that will be with your family for several generations, then this will likely not be the best paper for you.

The problem with these papers is analogous to the non-fibre based photographic papers we discussed above. The manufacturing process for paper includes acids. Without the elimination of those acids, the substrates are doomed to discoloration and fading. Unfortunately, these inkjet papers cannot be washed for several hours to eliminate those acids, therefore you must turn to inkjet papers that are acid-free.

Acid Free Papers

Since we already made note that you cannot spend hours washing the papers that you put through your inkjet printer, you must depend on others to do the washing for you. Epson, Canon, and HP all offer acid-free papers for their line of inkjet printers.

There are numerous third-party paper manufacturers that produce similar acid-free papers. It is during the manufacturing process that these papers have been subjected to extended washing and acid-neutralization materials.

These buffering agents, frequently calcium bicarbonate or magnesium bicarbonate, will build up a buffering reserve in the paper. This reserve is needed to ensure that the paper maintains its acid-free state after it ships. Some data indicates that these "alkaline" papers, that is the papers that have been treated with some form of carbonate, could have a life span of 500 to 1,000 years. This seems likely to be a point that will be of little concern to the average photographer.

If your printer will accept thicker substrates, there is no need to purchase a vendor-specific, acid-free paper. The owner’s manual and user guide for your printer will specify the thickness your printer can handle. You can go to your local art store and check out its many acid-free papers. These can also go by the description of “rag paper” or “museum paper.” They may have varying amounts of linen or cotton and may have any number of finishes to their surface. Depending on what effect you are looking for with your picture, this is an alternative to the printer vendor's papers. You might find a paper that you like, but it is sized larger than the print you plan to create. In this case, you must get it professionally cut to size, which incurs yet another cost.

This is the crux of creating your own photographic history. Without these papers, in conjunction with a printer that uses pigmented inks, your images stand diminished chances of passing into history intact.

The Color of 'White' Paper

When you look at a photograph, you likely believe that the color of the paper is white. And not just white, but pure white. Nothing could be further from the truth. And this factor is very important when it comes to archival-quality printing.

While you are at that art store we mentioned above, look at their many and varied acid-free papers. There will be a wide variety of shades of white. These could range from a bright white, sometimes called artic white, to a very subdued eggshell white. You need to be aware of this color of your substrates, because it will affect the final color of your print.

Whether your print is black-and-white or in color, substrate color will influence the way someone looks at your picture. It most likely will not be as pronounced as this old sepia-toned photograph, but you will see a difference if you try to reproduce your pictures with a sepia-tone appearance.

If your picture has sharp contrasts between the blacks and the whites, you may want to tone them down slightly with a paper that is less bright or a muted white. However, if you want to pump up that contrasty appearance, you may want to have the brightest white substrate available. This color choice doesn’t increase the print’s longevity, but it can help lend some style.

Mounting and Framing

You have created your print. You have used your pigmented-ink printer and printed your picture out on acid-free paper. Now you want to see your history hanging on a wall. All your efforts could be for naught if you poorly mount your photograph.

The last two items to ensure that your picture remains acid free is the mounting board and the mount tissue you use. Both need to be as free of acids as the paper. Unless you plan on doing dozens of pictures yourself, let someone else do this for you. A dry mount press, such as the one you see here, can cost from hundreds to thousands of dollars. Let someone else do this. Your job is to specify what type of mount board you want to use and ensure the mounting service is using acid-free mounting tissue. The tissue is the glue that lies between the print and the board. When heat and pressure are applied to the entire sandwich, your picture will become a permanent part of that entire mount. If you choose this procedure, consider that the cost will be dependent on the size of your print. You will also face choices about whether the print will be mounted flush to the edge of a board or whether it will be placed on an over-size board. Perhaps you’ll choose to have another board mounted around the photo to frame it. These decorative choices don’t lend longevity either, but again, they’ll add style for a fee.

There is also a less expensive alternative back at the art store. Ask for acid-free storage boxes. Lay your prints in the box and interleave them with an acid-free tissue.

Framing a photograph will likely be your last item to consider. A large number of photographs are framed in a simple brushed aluminum or flat-black aluminum frame. This is one aspect to preserving your photographic history that you can take on yourself. Buy the components and grab a screwdriver from the toolbox and follow the assembly instructions.

The Rest Is History

This may look like a daunting task at the start. But with the penchant today for preserving the memories of our daily lives with scrapbooks, social networking/storage sites, or even that old shoebox, you have several options to preserve your personal or family history in photographs.

While you may not be the next Matthew Brady or Ansel Adams, your photographic works are just as important to you. Your grandchildren and even your great-grandchildren deserve to see those historic moments from your lives. Take the time, do it right, and let your history live on. Using pigmented inks, printed on acid-free paper, will create prints designed to last at least 100 years and perhaps longer.

-

ebattleon There are archival class DVD media that have longer warrantied life spans than that mentioned in the article. Taiyo Yuden and TDK offer archive class DVDs' with life span of 70 years which is pretty good don't you think. It is implied that Laser Printers cannot be used for archive class photos, is this really the case?Reply -

zodiacfml i would rather see advice on preserving negatives or digital files since we only print when we need it and printing is improving constantly.Reply -

rockerrb This was a really really good article. I remember using Illford photographic paper in college in basic photography. We used an Iris printer for computer graphics printouts. It cost over $50k. I don't know what the shelf life of the prints is. I have them mounted on mat board in a portfolio which is in storage. These days you can make prints that are just as good or better for a lot less money.Reply -

davehcyj You should also mention that when framing a photo it is important to have UV filtering glass, since UV light can fade photos as well.Reply

It would have also been good to include in the article a section about getting the prints done somewhere. For people that will only need to do a small number of photos, the cost of the high end printers/inks might not be worth it. I don't know if places like Wal-Mart offer multiple paper choices, but there are many profession photo printing services available on the internet that give you a range of professional Kodak papers to choose from. These services have the added benefit of using million dollar printing machines which can produce higher quality prints than consumer printers especially if the home user isn't knowledgeable enough to properly calibrate the printer.

-

Do you have any information on a scalable solution to scan all those photos that you don't have negatives for? I know you can outsource it but since they are irreplaceable I hate mailing them away. Is there a place that you can bring a box of them and they scan them and hand the box back to you?Reply

-

Darkk Very good article. I have a Epson R380 Photo Printer and Epson 4490 Photo Scanner. Both devices work very well for what I use it for. It is a shame that alot of my relatives never kept the negatives as I could have scanned it with my scanner to produce photos for them to keep.Reply

Now these days we all take digital photography for granted. Just point and click. Then take the SD card home to a printer for instant gratification for something that would have taken hours to do. I think doing it the old fashioned way a few times would show true appreciation of photography as it was in the old days.

Case in point, pioneer photographers with monster box size cameras strapped to a donkey on a long trip whereas today we just whip the camera out of our pocket and take a quick snapshot. Boy, times sure have changed! LOL

-

Shadow703793 This should article should have been more prominent on the home page. One of the better written ones this month.Reply -

klyndt Good article. I would like to second the motion on adding information on getting the prints done by someone else. I am currently using Fotki because they claim to use archival quality inks and paper and I would be interested in seeing how they stack up to other firms. Also, I always thought that you couldn't print your own pictures for cheaper than an outside firm could. There are probably monetary advantages to going with someone else for printing. I think a follow-up article could be very interesting.Reply -

You should just go to a real photo lab and have your photos printed if you have any interest in having your prints last a lifetime.Reply

Why give money to the ink cartels? Seriously, they told us 10 years ago our prints would last a lifetime too. Why should we believe them this time around?

Chemistry prints are the way to go.

Club Benefits

Club Benefits