You're probably doing 2FA wrong: Here's the right way

The most common method for two-factor authentication is texted codes, but it's also the least secure.

Here at Tom’s Guide our expert editors are committed to bringing you the best news, reviews and guides to help you stay informed and ahead of the curve!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Tom's Guide Daily

Sign up to get the latest updates on all of your favorite content! From cutting-edge tech news and the hottest streaming buzz to unbeatable deals on the best products and in-depth reviews, we’ve got you covered.

Weekly on Thursday

Tom's AI Guide

Be AI savvy with your weekly newsletter summing up all the biggest AI news you need to know. Plus, analysis from our AI editor and tips on how to use the latest AI tools!

Weekly on Friday

Tom's iGuide

Unlock the vast world of Apple news straight to your inbox. With coverage on everything from exciting product launches to essential software updates, this is your go-to source for the latest updates on all the best Apple content.

Weekly on Monday

Tom's Streaming Guide

Our weekly newsletter is expertly crafted to immerse you in the world of streaming. Stay updated on the latest releases and our top recommendations across your favorite streaming platforms.

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Google, Facebook, Apple, Microsoft, Dropbox and many other online services offer two-factor authentication (2FA) as an option to protect your account.

With 2FA enabled, it's much harder for a crook to break into your account, even if he or she knows or can guess your password, because the crook will be missing that crucial second factor that only you possess. We at Tom's Guide urge our readers to enable 2FA whenever they can.

- The best password managers

- How to get a better two-factor authentication key for $20

- Passwords aren't dead — you're just using them wrong

But there are several different forms of two-factor authentication, and, unfortunately, you're probably using the worst one. Here's how to beef up your 2FA game.

Two-factor authentication consists of providing a second form of authentication after you enter your username and password when logging in to an online account.

The second form of authentication, or factor, can't just be another password or PIN. It's got to be tied to something that you alone have, such as a smartphone or a hardware security key, or a unique physical attribute, such as your fingerprint or your face.

Least safe 2FA

— Texted or voice-called codes: The most common second factor for 2FA is a temporary four- or six-character digital or alphabetic code texted via SMS to your mobile phone. The code is automatically generated by the service you're logging in to and is good for only a short time, usually less than 5 minutes. A variation is to have an automated phone call read out the code out to you, which also works with land lines.

This may be the kind of 2FA you have, but it's also the least secure form. Text messages and voice calls aren't encrypted, and they're tied to your phone number rather than to a specific device. They can be intercepted by anyone who has stolen your phone number, who has changed your account to forward calls or texts to a second number, or who works at the phone carrier. You also need to have working cellular service for the texts to work at all.

Get instant access to breaking news, the hottest reviews, great deals and helpful tips.

SMS-based and voice-based 2FA are better than no 2FA at all, and many online services give you no other choice. There are better second factors available, however, some of them just as easy to set up as the texted-code system.

Safer 2FA

— Push codes: These are temporary codes sent over encrypted internet connections, rather than phone lines, to an app on your smartphone or to the phone's operating system. Apple does this with iPhones, iPads and iPod Touch devices running iOS 9 or later. (Android devices and older iPhones using Apple 2FA have to stick to SMS-based codes.)

— Code-generating hardware tokens: If you worked in a big company 10 or 15 years ago, you may have been given a little doohickey for your keychain that displayed a new six-digit number every 30 seconds. You typed in that number whenever you logged in to your workplace network from home or while traveling. These aren't used much anymore, because it's easier to generate codes on smartphones.

— Code-generating authenticator apps: Temporary verification codes don't need to be sent to you; they can be generated right on your phone. Dozens of authenticator apps do this, and many of them are free. The best-known are Authy, Duo Mobile, Google Authenticator, LastPass Authenticator and Microsoft Authenticator.

Many online services — including Amazon, Dropbox, Facebook, Google, PayPal, Slack and Twitter — support authenticator-generated codes as an alternative to SMS-based codes. All the apps can be used for multiple accounts, and you don't need to have a cellular connection, or even Wi-Fi access, on your phone for the codes to work.

Setting up an authenticator app is easy. Log in to an online service on a desktop or laptop web browser, go to your security settings, and indicate that you want to set up an authenticator app for 2FA. The site will show you a QR code, which you capture in the authenticator app on your phone using your phone's camera. That should do it.

However, no form of 2FA using temporary codes is immune to phishing attacks. Crafty criminals can fool you with a phony website that looks like the one where you're supposed to type. The criminal then collects the code you enter and types it into the real site. Such attacks have been successful against Google accounts.

Even safer still

— Push approvals: What if you could just tap "Yes" or a checkmark on your phone rather than typing in a code? Microsoft offers this with its Microsoft Authenticator app; Yahoo has it built in to its Yahoo Mail app; and Google builds it right in to Android for G Suite enterprise users.

The catch is that you have to be logging in to your Microsoft, Yahoo or G Suite accounts, respectively. However, many third-party authenticator apps, including Authy and Duo Mobile, can handle push notifications for multiple services.

Also, malicious Android apps could mimic or hijack push notifications and get the user to mistakenly approve unauthorized account logins. This is less of a problem with iOS devices.

Safest 2FA of all

— USB security keys: These are small, key-shaped devices, also called hardware security keys, that you plug into a computer's USB port when you're logging in to a website from a new computer. Some security keys also sport near-field-communications (NFC) to interact with smartphones.

The best-known USB security keys are made by Yubico and are called YubiKeys, but there are several other manufacturers and a few different standards. The basic standards are universal second factor (U2F) and WebAuthn, and they're the most widely supported ones.

To set up a USB security key, you register it with an online service from a computer that the service already "trusts." You can use a single key with more than one account, and a single account can register more than one key.

Unfortunately, support for hardware security keys isn't widespread yet. Google supports U2F-based keys, as do Dropbox, Facebook and Twitter, but not many other online services offer this.

The most widespread support is found with password managers: Dashlane and Keeper support U2F keys, while LastPass and 1Password support Yubico's own standard.

The other downside is that USB security keys cost money. Prices range from $8 for the HyperFIDO U2F key without NFC to $60 for Yubico's tiny USB-C YubiKey Nano. The best deal may be a $17 U2F key with NFC from Feitian, identical to what Google sometimes sells as part of its Titan security key bundle.

If you get a USB security key, you should get a second one as a backup in case you lose the first. Despite the cost and the limited support (for now), USB security keys are the best and safest second factor for 2FA.

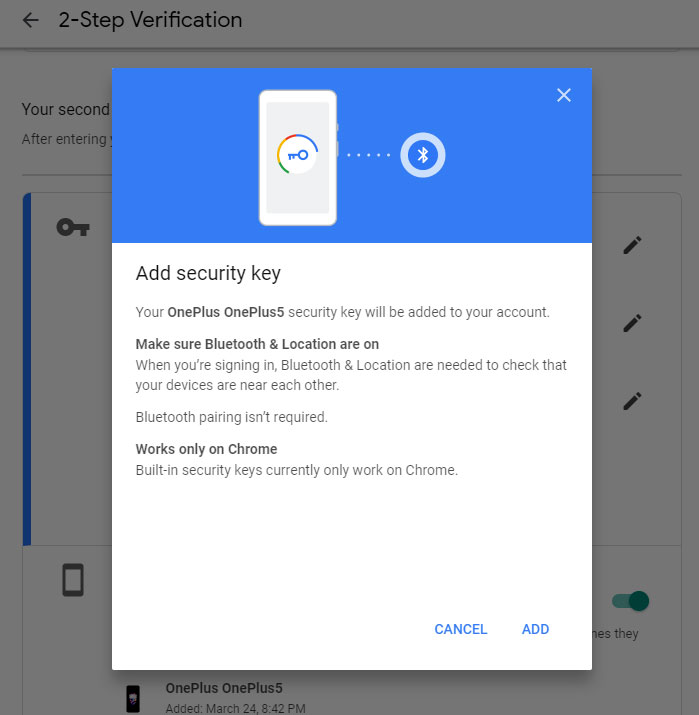

— Your Android phone: As of April 2019, Google lets you register a phone running Android 7 Nougat or later as a security key. The registration process (detailed instructions are here) is the same as that for setting up a USB security key, but you select a compatible Android phone instead of a key.

There are some catches: This will work only for your Google account; you have to log into the account using the Chrome desktop browser on a computer running Windows 10, macOS or Chrome OS (no Linux, apparently); and both the computer and your Android phone need to have Bluetooth turned on. (They don't need to be paired.)

After you input your username and password into the desktop browser, you will be asked to interact with your Android phone. If you have a Google Pixel 3 phone, you can simply click the volume-down button.

For other Android phones, you will need to respond to a push notification on the phone's screen. (This is safer than the regular push notification you get with G Suite, as the phone has to be within Bluetooth range of the computer you're logging into.)

For the future

— Biometrics: Let's not forget the unique identifiers you were born with: your fingerprints, your iris patterns and your face. At the moment, these are mostly used to log in to devices locally, such as by using your face or fingerprint to unlock your smartphone or laptop screen (as long as your laptop supports Microsoft's Windows Hello).

But with the new FIDO2 standard, biometrics can be used to log in to online services as well. The best current example of this is Microsoft, which lets you log in to any of its online services using a Windows Hello-compatible computer. A few USB security keys sport fingerprint readers for use with Windows Hello.

No password is needed for regular usage, although you will need to use your Microsoft password to set this system up on a new devices. Microsoft Edge, Google Chrome and Mozilla Firefox also support FIDO2, but few non-Microsoft online services yet do.

We're not quite at the point where you can set up 2FA itself without a password. But you can expect to see that in the future as FIDO2 and standardized biometric formats catch on.

Paul Wagenseil is a senior editor at Tom's Guide focused on security and privacy. He has also been a dishwasher, fry cook, long-haul driver, code monkey and video editor. He's been rooting around in the information-security space for more than 15 years at FoxNews.com, SecurityNewsDaily, TechNewsDaily and Tom's Guide, has presented talks at the ShmooCon, DerbyCon and BSides Las Vegas hacker conferences, shown up in random TV news spots and even moderated a panel discussion at the CEDIA home-technology conference. You can follow his rants on Twitter at @snd_wagenseil.

Club Benefits

Club Benefits