Amazon’s Sidewalk developer kit just revealed how many of my neighbors use Ring and Alexa

Amazon has quietly deployed a huge network

Here at Tom’s Guide our expert editors are committed to bringing you the best news, reviews and guides to help you stay informed and ahead of the curve!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Tom's Guide Daily

Sign up to get the latest updates on all of your favorite content! From cutting-edge tech news and the hottest streaming buzz to unbeatable deals on the best products and in-depth reviews, we’ve got you covered.

Weekly on Thursday

Tom's AI Guide

Be AI savvy with your weekly newsletter summing up all the biggest AI news you need to know. Plus, analysis from our AI editor and tips on how to use the latest AI tools!

Weekly on Friday

Tom's iGuide

Unlock the vast world of Apple news straight to your inbox. With coverage on everything from exciting product launches to essential software updates, this is your go-to source for the latest updates on all the best Apple content.

Weekly on Monday

Tom's Streaming Guide

Our weekly newsletter is expertly crafted to immerse you in the world of streaming. Stay updated on the latest releases and our top recommendations across your favorite streaming platforms.

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

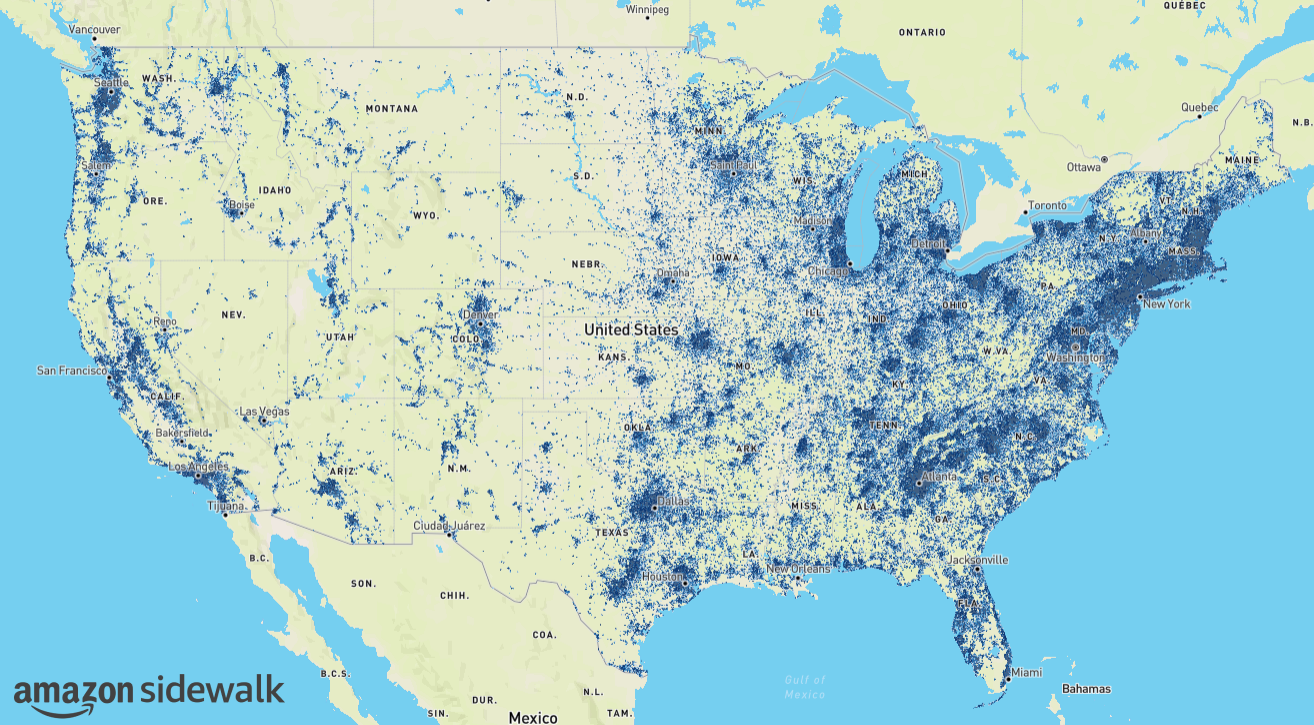

Amazon has slowly been building a new wireless network, and it's ready to show the world how pervasive it is. Almost three years ago, Amazon announced the launch of Amazon Sidewalk, a low-power, low-bandwidth wireless network that would enable more devices to connect to the Internet.

But how do you build an entirely new wireless network without putting up signal repeaters and cell towers? In the case of Amazon, you simply build it into every Alexa and Ring device you can, which the company has done since 2018.

In order to encourage developers to start creating devices that can work with the Sidewalk network, Amazon announced a Sidewalk developer kit, which lets you see just how far its network has spread. Amazon sent me the test kit to try out, and I was astounded by how many of my neighbors have an Alexa or Ring device.

First, a brief example of how Sidewalk works.

Imagine if you had a Tile tracker with Sidewalk built in. Whenever the tracker came within range of a Sidewalk network — say, an Amazon Echo — it could transmit its location data to the Echo, which would then use a tiny part of your Internet connection to send that data to the cloud, so you could know where your Tile tracker is. It's potentially much more useful than waiting for it to come within range of a Bluetooth device, or, in the case of Apple's AirTag, an iPhone, pervasive as those may be.

Amazon envisions Sidewalk will be used for much more than that, though. “We’ve rapidly built out a long-range, low-bandwidth network that now covers more than 90% of the U.S. population, and this is an open invitation for developers to put it to the test,” said Dave Limp, senior vice president of Amazon Devices & Services in a press release. “Sidewalk is designed to provide a secure, low-cost way to invent and connect a whole new range of devices.”

For example, Amazon is testing Sidewalk with Arizona State University to extend the range of sunlight, temperature, CO2 detectors, and particle counters across its campus. Closer to home, a Sidewalk-enabled device might be a smart lock or smart lights on your property.

Get instant access to breaking news, the hottest reviews, great deals and helpful tips.

When it was announced, many — including myself — were understandably concerned about how this would work. Not only am I loath to donate part of my bandwidth to Amazon, but I'm not thrilled with the idea of some random device being able to hop onto my home network.

On its Sidewalk page, Amazon states that a Sidewalk Bridge uses a maximum of 80Kbps, and that Amazon caps the amount of data used by Sidewalk at 500MB. Also, Sidewalk devices don't get access to your Wi-Fi network, and any data coming from a Sidewalk device is encrypted.

Still got the heebie jeebies? You can turn off Sidewalk on any of your devices.

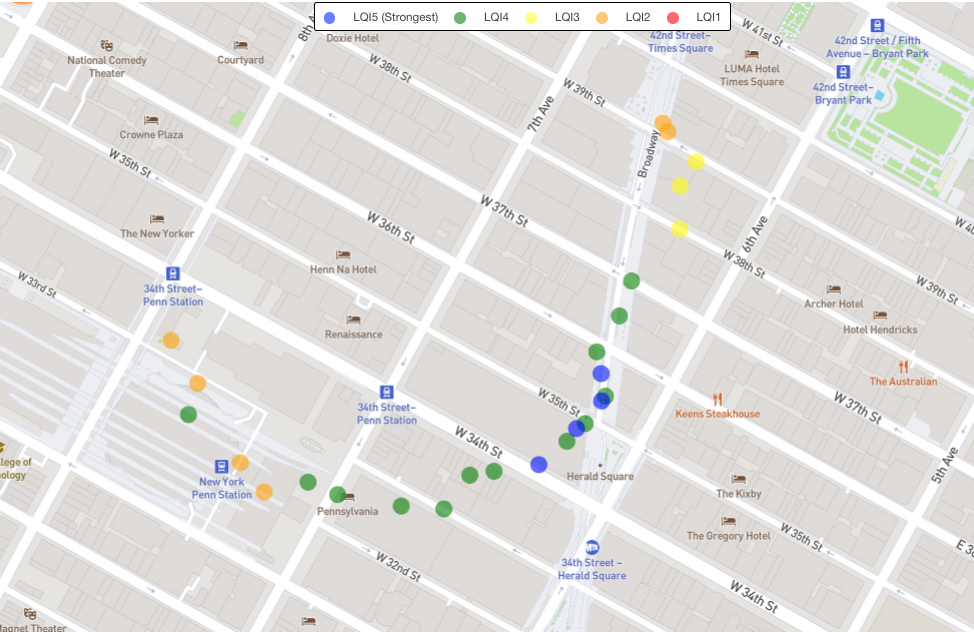

The test kit Amazon sent me is a small dongle, not much bigger than a USB thumb drive. Inside is a GPS module and a Sidewalk sensor; all I had to do was take a stroll through my neighborhood, and the device would record the relative signal strength of the Sidewalk network, and then upload it to a private test kit coverage map.

I'm not going to post a photo of the map to protect my neighbors' privacy, but suffice it to say that it looks like a significant number of people have Alexa or Ring devices with an active Sidewalk network.

A bit concerned with what I found, I asked an Amazon representative about my findings. "Preserving customer privacy and security is foundational to how we’ve built Amazon Sidewalk," they said. "Developers must register and sign agreements before they can receive a test kit. They will need to provide a valid address, phone number, and other verifying developer details. This allows us to take appropriate action if the test kits are misused, including turning off the test kits."

Additionally, they mentioned that a strong signal in front of a person's house might not necessarily indicate they have an Alexa or Ring device.

"By design, the RSSI signal does not provide a precise measurement or enough granularity to pinpoint a specific location of a Sidewalk Bridge device," the representative said. "The test kit ping that goes over Sidewalk doesn’t necessarily go to the closest Sidewalk Bridge device—these messages are capable of being sent over several miles."

"It also depends on where and when the Bridge device sends the signal to the cloud. Thus, the individual pings you’re seeing on the map may be sent from a wide number of Sidewalk Bridge devices rather than just the house you pass by. For example, if you’re walking around your neighborhood and find a location that has a high RSSI number, the ping you’re seeing on the map could stem from a Ring Floodlight Cam that’s 600m away, or even an Echo Plus that’s sitting in a high-rise building."

Regardless of where the signal was coming from, it seemed to be pretty strong all around my town. I also used it when traveling to my office in midtown Manhattan, and though the sample size was smaller, there appeared to be fairly good coverage, though not inside my office building, where it seemed to stop tracking Sidewalk entirely. That's not entirely surprising, as there are far fewer local residences — and fewer opportunities to install an Amazon Echo or Ring — and I suspect that all of the high rises most likely interfere with the Sidewalk signal, much as they do with 5G cell service.

My neck of the world isn't necessarily indicative of the rest of the U.S., but from what I could see, Amazon's Sidewalk is — or has become — one of the largest networks in the country. You just don't know it yet.

More from Tom's Guide

Michael A. Prospero is the U.S. Editor-in-Chief for Tom’s Guide. He oversees all evergreen content and oversees the Homes, Smart Home, and Fitness/Wearables categories for the site. In his spare time, he also tests out the latest drones, electric scooters, and smart home gadgets, such as video doorbells. Before his tenure at Tom's Guide, he was the Reviews Editor for Laptop Magazine, a reporter at Fast Company, the Times of Trenton, and, many eons back, an intern at George magazine. He received his undergraduate degree from Boston College, where he worked on the campus newspaper The Heights, and then attended the Columbia University school of Journalism. When he’s not testing out the latest running watch, electric scooter, or skiing or training for a marathon, he’s probably using the latest sous vide machine, smoker, or pizza oven, to the delight — or chagrin — of his family.

Club Benefits

Club Benefits