CISA Set to Become Law: Don't Panic Yet

The controversial CISA bill is set to become law as part of a spending package. Here's what's in the final version, and what it means.

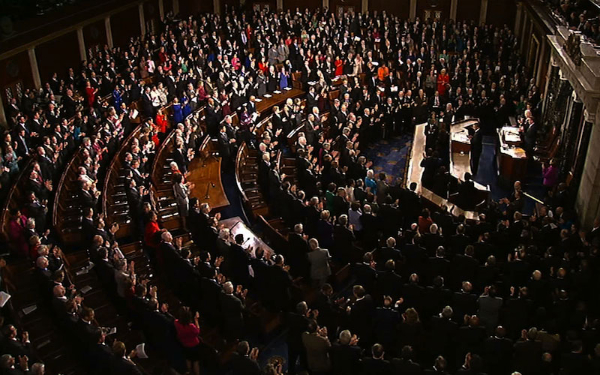

The controversial Cybersecurity Information Sharing Act (CISA) now seems almost certain to become law, after House and Senate negotiators managed to insert its latest version into an omnibus spending bill last night (Dec. 15). The spending bill, 2,000 pages long, governs a large part of the 2016 federal budget, and both houses of Congress, as well as the White House, are eager to make it law by early next week.

Digital-privacy advocates, who had hoped to see CISA defeated, decried the bill as a secret step toward a national-security state.

"It's a disingenuous attempt to quietly expand the U.S. government's surveillance programs," said Fight for the Future, a group that has issued nearly-daily emails warning about CISA in apocalyptic tones.

CISA "would expand government surveillance under the guise of protecting cybersecurity," said the American Civil Liberties Union. "This would allow companies to share large amounts of private consumer information with government agencies, including possibly the FBI and NSA."

But the reality of CISA — the text is on pages 1728-1863 of the omnibus bill — is much more boring. It creates a legal framework by which private companies and organizations, as well as state and local governments, can voluntarily share information about designated "cyber threats" with the federal government in secret, without risk of resulting liability or regulation. It also incorporates many privacy safeguards designed to strip personal details from the shared information.

MORE: The CISA Bill: Everything You Need to Know

Advocates of CISA argue that such legislation is necessary because, with almost all of the American Internet infrastructure in private hands, companies need to be able to communicate freely with the federal government about cybersecurity.

Get instant access to breaking news, the hottest reviews, great deals and helpful tips.

Right now, the argument goes, two companies whose networks were simultaneously under attack by the same third party would not be able to fully share information with federal agencies, or each other, without opening themselves up to lawsuits from shareholders, customers or regulators.

CISA designates the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), regarded as having strong privacy regulations, as the gatekeeper of information received from private entities or non-Federal government agencies. DHS is required to strip the received data of personal details pertaining to individuals before passing it on to other federal agencies.

The final version of the bill is a compromise reconciling differences among three bills — an earlier version of CISA that passed the Senate in October, and two similar bills that passed the House in April. House and Senate negotiators spent much of the past week behind closed doors hammering out the reconciled version, and managed to add it to the omnibus spending bill at the last minute. Had they not done so, full-chamber votes on CISA as a stand-alone bill would probably have not been held until January.

The final version potentially weakens DHS's role as gatekeeper of information by giving the president discretionary authority to designate another federal agency as gatekeeper alongside DHS. However, that second agency cannot be part of the Department of Defense, which includes the National Security Agency (NSA). The president will be able to do this without the approval of Congress, although he or she must notify Congress beforehand and explain the reasons behind the decision.

The bill also permits information shared with the government to be used in prosecuting certain cases not pertaining to cybersecurity. These are defined as cases involving specific threats of death, "serious bodily harm" or "serious economic harm," including terrorist acts, cases involving "a serious threat to a minor," as well as cases involving fraud, identity theft, espionage, censorship and "protection of trade secrets." Such language is vague enough to be stretched to fit many possible scenarios.

But the bill leaves out much of what national-security hardliners in Congress had wanted, such as the enabling of direct communications between private companies and agencies other than DHS, such as the FBI, the CIA or the NSA.

Unless the president decides to exercise the discretionary power mentioned above, such direct communications will be permitted only in the cases of existing relationships, regular regulatory matters or when they pertain to ongoing cases in which the initial communications have passed through DHS.

The most cogent argument against CISA may not be that it places too many restrictions upon information sharing, or that it fails to adequately protect individual privacy, but that it could be redundant. A host of other legal frameworks for information-sharing between government and private industry already exist. However, none have CISA's blanket provisions for immunity from liability or regulation.

Like much contentious legislation, the final version of CISA may make nobody happy, but it may leave many people begrudgingly satisfied.

Paul Wagenseil is a senior editor at Tom's Guide focused on security and privacy. He has also been a dishwasher, fry cook, long-haul driver, code monkey and video editor. He's been rooting around in the information-security space for more than 15 years at FoxNews.com, SecurityNewsDaily, TechNewsDaily and Tom's Guide, has presented talks at the ShmooCon, DerbyCon and BSides Las Vegas hacker conferences, shown up in random TV news spots and even moderated a panel discussion at the CEDIA home-technology conference. You can follow his rants on Twitter at @snd_wagenseil.

-

HEXiT this is messed up. private interests trying to buy laws isnt good for democracy and certainly not good for the internet as a whole.Reply -

Mickey_4 What it sounds like to me is that it allows websites to violate their own privacy agreement in the interest of security. The only thing stopping a website from sharing information with any agency, whether federal or private, is the privacy agreement. If a company wants to share that kind of information, why not include a clause in their privacy agreement about sharing information in the event that the information may prevent violence or security issues.Reply

Club Benefits

Club Benefits