Legal? PlayLater Lets You Record All of Netflix for $20

Using PlayLater, you can take advantage of cheap software and free trials to get months' worth of video content. But how legal is it?

Watching TV and movies in the modern world is a delicate balancing act among convenience, price and morality. For example: Is it OK to skimp on subscription fees by building a vast library of recorded programs from paid services like Netflix, Hulu Plus and Amazon Prime? Is it even legal?

It's a question that occurred to me a few months ago as I fell in love with The Thick of It, a sharp-tongued British political comedy starring Peter Capaldi, of Doctor Who fame. I was about halfway through the show on a Hulu Plus trial, but knew I'd never be able to finish it before the end of my free month.

MORE: Best Streaming Video Services

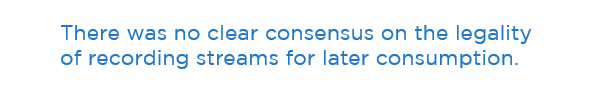

"But what if…?" I thought, as I opened the PlayLater program on my PC. PlayLater ($20 per year) is a program that records video from streaming services locally onto your computer. From there, you can play the programs on your computer, tablet, game console, TV, streaming box or anywhere else that supports digital video, no Internet connection required.

Theoretically, you could sign up for free one-month trials to Netflix, Hulu Plus and Amazon Prime, amass a huge library of content using PlayLater, then cancel your subscription before paying a dime. One month of each service would add up to almost 3,000 45-minute TV episodes.

I've used PlayLater for about two years, and it has been an absolute godsend when traveling on the subway or an airplane. This, however, was the first time I realized that the platform could exist in some legally murky waters.

I did some investigating to find out what you can legally do with PlayLater and what you can't (or at least probably shouldn't) do. The answers vary wildly depending on whom you ask.

Get instant access to breaking news, the hottest reviews, great deals and helpful tips.

What Do the Terms of Service Say?

PlayLater can record videos from many streaming services, like HBO Go, Nickelodeon, ABC and Food Network. Some require subscriptions, and the terms of service vary significantly for each service. For simplicity's sake, let's examine the big three: Netflix, Hulu Plus and Amazon Instant Video. Forgetting legality for a moment, let's just see if these providers' terms of service permit recording video.

In two out of three cases, the answer is clearly no. Netflix and Hulu Plus specifically state that users cannot download videos for personal use, while Amazon Prime does not discuss third-party downloads.

Downloading videos "is a clear violation of the terms of service," said Cliff Edwards, director of corporate communications and technology at Netflix. "Our licensing agreements don't allow companies [like PlayLater] to facilitate these types of uses," he told me.

Technically, if you violate a product's terms of service, you may have broken a legally binding contract. However, it's not clear if a streaming video company's terms of service supersede the concept of fair use (if recording digital video counts as fair use at all), or whether these terms are enforceable.

It Was Legal for VCRs

While I don't recommend violating a product's terms of service, I also don't want to give the impression that such a practice is inherently illegal or unethical. I conferred with representatives from Netflix and PlayLater, as well as two legal experts, and found that there was no clear consensus on the legality of recording streams for later consumption.

"If I'm using a VCR to record an episode of Star Trek to watch later, that's time-shifting," explained, Sherwin Siy, vice president of legal affairs at Public Knowledge, a nonprofit that specializes in intellectual property law. "The Supreme Court has said that [time-shifting] is fair use."

Siy described Sony Corp. of America v. Universal City Studios, Inc., better known as the Betamax Case, which went before the Supreme Court in 1984. The court ruled that using VHS tapes (or similar technologies) for time-shifting purposes did not constitute copyright infringement.

Recording your favorite show and watching it later is perfectly legal — at least in an analog format. Time-shifting content in a digital format became a very complicated issue after American Broadcasting Companies v. Aereo, a case that went before the Supreme Court in 2014.

Why the Aereo Case Complicates Matters

Aereo was a service that received broadcast TV by antenna and then transmitted the video over the Internet for a subscription fee. The Supreme Court ruled that Aereo's retransmission constituted a "public performance" of copyrighted works and was therefore copyright infringement.

Streaming providers do not broadcast live TV. But using a middleman program like PlayLater to record content may still count as a "public" broadcast, even though only the end user records and ultimately sees the content. Not even the Supreme Court is 100-percent sure.

"We cannot now answer more precisely how [provisions of the Copyright Act] will apply to technologies not before us," wrote Justice Stephen Breyer in the Supreme Court's majority opinion on the Aereo case. Bryer then quoted, and said the Court supported, an opinion from the Justice Department that, "Questions involving cloud computing, DVRs, [remote storage] and other novel issues not before the court … should await a case in which they are squarely presented."

Adventures in Time- and Space-Shifting

As if the issue were not already complex enough, there is one other factor to consider: time-shifting versus device- or space-shifting. The Supreme Court ruled that users could record broadcast content to watch at their leisure, but recording content to watch on a different device, like a tablet or a game console, was outside the scope of a 1984 ruling.

Device-shifting may well be legal, but no one knows for sure. "Shifting something from one device to another, that's a case that hasn't gotten to the Supreme Court yet," Siy said.

MORE: Your Guide to Cable TV Cord Cutting

Erik Stallman said he is similarly unsure. Stallman is the director of the Open Internet Project at the Center for Democracy and Technology, a nonprofit that protects consumer rights online.

"You've got a good claim for the legality of time-shifting or space-shifting under the Sony Betamax case," he said. "We're not really sure how much of that is still good law after Aereo."

That does not mean that users have a carte blanche to record streaming content. "You still face potential liability under terms of the contract," Stallman explained. "You don't own that copy outright. You just licensed it for a limited purpose. That does not include recording it."

Play (How Much) Later?

Time-shifting and device-shifting still lie at the crux of the issue. Does PlayLater violate the Hulu and Netflix terms of service? Yes. But is it illegal? Does it vary significantly from recording a program with a VCR or a DVR box?

The answer is a resounding maybe, but "maybe" is not enough to prosecute. It's probably not even enough to get you kicked off of a streaming service. Until the Supreme Court determines exactly what constitutes fair use for time-shifting and device-shifting, consumers have a lot of leeway with how they consume content online.

I asked Siy and Stallman about the idea of using PlayLater to record an entire series while on a trial subscription. Their answers differed somewhat.

"There are some hints in the [Supreme Court's] language that suggest it's not fair use" to record a series in this way, Siy explained. "But they didn't rule on it either way. Using [PlayLater] so you can watch something on the go is fine, but if you want to stay on the right side of the law, don't use it to amass a collection of things and then cancel the subscription."

Stallman said he was not sure that scale entered into the equation. "There's no clear line that once you record a certain amount of content to watch later, or you've done this with a trial subscription rather than a regular subscription, that it really affects fair-use analysis," he said. If recording one video is fair use, Stallman suggested, recording 1,000 of them may be fair use as well.

I asked Jim Holland, a marketing representative for PlayLater, whether the company sees a distinction between recording videos for one-off use and building up a collection.

"Consumer fair use allows for you to time-shift content," he said. "PlayLater is protected by the same statutes that protect the DVR and the VCR before it. If you are recording online content that is legally available to you for the purposes of viewing that content at a time of your choosing, that is perfectly legal."

Holland's viewpoint appears to be unequivocal: PlayLater allows time-shifting, time-shifting is upheld by the Supreme Court, and the scope of the project is irrelevant.

Could You Be Sued?

Ultimately, users have to ask themselves a very important question if they want to use PlayLater: Could they get in trouble?

Stallman pointed out that if Netflix could track which of its customers used PlayLater, it could nail those users for violating terms of service.

I asked Edwards if this could happen, and he said it was not likely. "I would guess no," he said. Since PlayLater makes no attempt to mask a user's IP and channels Netflix through a user's computer, it would probably not appear any different to the company than a user simply watching a video. Watching a few dozen in a row may seem suspicious, but there is nothing in the Netflix terms of service that forbids a user from running the streaming channel 24/7 in the background.

MORE: Best Streaming Players: Chromecast, Roku, Apple TV & More

Moreover, using PlayLater to record a few episodes for a subway or plane ride here and there is far beneath the notice of any big company. If every streaming user built up a library, it could have harmful repercussions on a service's profits. Time-shifting individual episodes would not.

"If it's just a matter of you making a copy of this stream, and it's only for you, as a practical matter, the situation isn't that much different than someone recording something off broadcast television," Stallman said. "If you copied every Star Trek episode ever, that's a question of having a significant effect on the market."

Siy reminded me that any technology that exists in a legal gray area may draw enterprising lawyers. "If someone wanted to make a big stink about it, they could," Siy warned. "It's unlikely that anyone would sue … at this stage, but there are always people willing to try."

Legally in the Thick of It

My ultimate goal was to answer one simple question: Can you record licensed content with PlayLater for personal use? Netflix says no. PlayLater says yes. The legal experts say maybe.

On the other hand, should you do so? It’s not my place to decide. Neither Tom's Guide nor I advocate taking actions that could potentially violate copyright. I am not an expert on copyright law, and those to whom I spoke offered their insight, not their legal counsel.

Edwards, Holland, Siy and Stallman agreed on exactly one thing, which is that their opinions do not constitute legal advice, and that they do not advise customers one way or another. If you have serious questions about using PlayLater to record video or build a library, it's best to consult a lawyer.

As for me, I eventually decided to shell out for a few more months of Hulu Plus to finish watching the show. Some things in life are worth paying for.

Correction: This article was updated at 10:13 ET, April 20 because it originally misquoted a Netflix spokesman on the company's interpretation of copyright law.

- Best TVs for Every Budget

- How to Watch Live TV Online

- How to Stream Video to a TV from a Mobile Device or Computer

Marshall Honorof is a senior writer for Tom's Guide. Contact him at mhonorof@tomsguide.com. Follow him @marshallhonorof. Follow us @tomsguide, on Facebook and on Google+.

Marshall Honorof was a senior editor for Tom's Guide, overseeing the site's coverage of gaming hardware and software. He comes from a science writing background, having studied paleomammalogy, biological anthropology, and the history of science and technology. After hours, you can find him practicing taekwondo or doing deep dives on classic sci-fi.

-

If you're going to go through the trouble of recording things to play later to pay less, might as well pirate the stuff from the start.Reply

Play later seems like a wannabe gangster. Except the rare scenario (subway, airplane, and ...) where you don't have internet, it has no use-case. -

hausjam The content providers could make this whole point irrelevant by allowing in-app caching for offline use. But that won't happen because I am certain AT&T, Verizon, etc are keeping behind-the-scenes pressure on the providers to not all this so they can continue to collect their overage fees.Reply

Look at music; MixRadio and Amazon both allow you to cache music for offline listening. I am betting the carriers let this go because music uses only a fraction of the data that video does. -

Marshall Honorof ReplyPlay later seems like a wannabe gangster. Except the rare scenario (subway, airplane, and ...) where you don't have internet, it has no use-case.

You make a fair point, but I don't think the rare scenario is quite as rare as you make it out to be. I ride the subway for about forty minutes every day, and travel on long flights about six or seven times a year. I initially subscribed to PlayLater because I wanted to access streaming content without being tethered to a Wi-Fi connection.

I could have pirated it, but the creators don't get any money that way. I figure that with PlayLater, at least I'm still making use of a subscription that I pay for, just shifting the content in a way that's more convenient to consume. Is it legal? Maybe. That's one of the reasons I was interested in writing the piece.

-

pahbi I just don't see how you can make a time shift argument for content that is available on demand anytime you are online.Reply

- P

-

bigpinkdragon286 There doesn't appear to be a time-shifting argument being made for places that have adequate online connectivity.Reply

There also doesn't seem to be an argument for the ISPs not wanting time shifting, as you have to transfer the bits through their infrastructure, whether you watch it via a live stream or buffered.

It's really an issue that could be solved, if those with the capacity would simply wrap their heads around it enough to do so. -

firefoxx04 I would rather pirate high quality bluray rips than crappy compressed netflix video. Netflix is good for on demand movie and tv show watching, not for building a movie collection.Reply

This service is certainly not legal and will get destroyed by Netflix and all its TV and Movie partners. -

bollwerk ReplyIf you're going to go through the trouble of recording things to play later to pay less, might as well pirate the stuff from the start.

In the case of Netflix, I disagree. Netflix will have shows or movies for a limited time, then their "lease" expires, so the show or movie is no longer available. I don't know if it's like that with other services, but I can see the potential for using this with Netflix, even if you keep a subscription with them.

Play later seems like a wannabe gangster. Except the rare scenario (subway, airplane, and ...) where you don't have internet, it has no use-case. -

Josh Argh You're comparing PlayLater to recording a show with a VCR, but your Netflix content is ALREADY a recording, and the internet is your VCR.Reply

The product you describe sounds more like duping your rentals from Blockbuster before returning them. In other words, clearly not fair use. You are not entitled to watch any content you want, anywhere, forever, on any device, because you rented it one time 20 years ago!

But, if you went to the trouble to buy two VCRs and didn't resell your copies, who cares? I think the same applies here. If you really want to be a cheapskate and screw the people who make that content, I guess you could leave a second computer running all month just to download Netflix streams, as long as it's just for you. Don't forget to give raisins to kids on Halloween! -

f-14 this was already covered in the 70's and 80's with radio air play, the supreme court made it's ruling then, and that ruling will stand as the premiere precedent in america.Reply

nothing in this argument has changed from the cassette era. -

JonnyDough So these corporations want me to pay to view every time. They want to own the show and never let me keep it. If it was up to them they'd be clearing our memory too so we could pay them to watch something over and over and give away money each time.Reply

Club Benefits

Club Benefits