How to Compose Your Own Music for Free

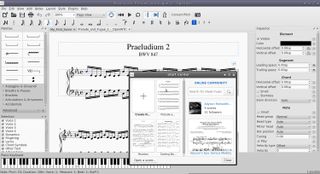

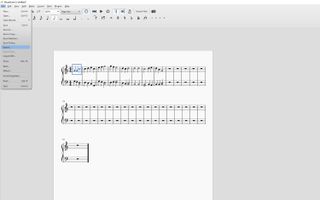

Thanks to a free program called MuseScore, you can compose, arrange and even listen to your very own masterworks.

If you've ever listened to "Messiah," George Frideric Handel's magnum opus oratorio, you may be surprised to learn that he wrote the entire piece in 24 days. That's four choral parts, four solos and a full orchestration, written with a pen and paper, often by candlelight. In the same period of time, I was able to compose a 1-minute TV-style theme song. But the good news is that you can, too!

Thanks to a free program called MuseScore, you can compose, arrange and even listen to your very own masterworks, provided you have a basic knowledge of musical notation and theory. The only problem is that, due to the plethora of options at your disposal, MuseScore is not always the easiest program to use. For newcomers, the intricate interface and touchy input controls may even seem daunting. But with a little creativity and a lot of patience, you, too, can unleash your inner Mozart — or at least your inner Salieri.

Why compose?

Before I sat down with MuseScore a few weeks ago, I hadn't composed anything in nine years. Although I dabble in a few instruments and know how to sing, I've never been formally educated in music theory. I can read music just fine, but the prospect of actually sitting down to create my own was just shy of terrifying.

But for the past few months, I have been running a pencil-and-paper Star Trek RPG, courtesy of the fine folks at Modiphius. And any experienced Game Master knows that a few well-placed extras can make the difference between a fun session and an experience you'll remember for years. Every Star Trek show has a theme song that sets the tone of the adventure; shouldn't mine?

I set to work hunting down a program. MuseScore isn't the only free composition program out there, but I found it a little more approachable than Noteflight or Finale Notepad. I also use a PC, so I don't have access to Apple's GarageBand. In a few weeks, the program would take me from humming motifs to myself at work to having an honest-to-goodness theme song just waiting to be married to Adobe Premiere opening credits. (One thing at a time, though.)

First things first

Before you even open up MuseScore, you'll need a working knowledge of musical notation and music theory. If you don't have the former, MuseScore's keyboard option can at least help you get notes on a page. If you don't have the latter, you can kind of fake it by listening to a lot of music and paying attention to how it sounds. But, just as you need to study rhetoric before writing a novel, you'll need the right tools to get what's in your head down on (digital) paper.

(Here's a good litmus test: Do you get why Homer Simpson's barbershop quartet calling itself The Be Sharps is funny? If so, you're good to go.)

Sign up to get the BEST of Tom’s Guide direct to your inbox.

Upgrade your life with a daily dose of the biggest tech news, lifestyle hacks and our curated analysis. Be the first to know about cutting-edge gadgets and the hottest deals.

With that out of the way, getting started is easy enough. Download MuseScore; then install it. Note that when you first install the program, you'll see a prewritten piece, which explains the basics of the program in an interactive fashion. This is an excellent resource — but after I closed it, I was never able to find it again. Assume that you'll have to do without it, although the program maintains a helpful how-to database online.

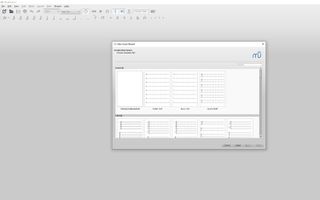

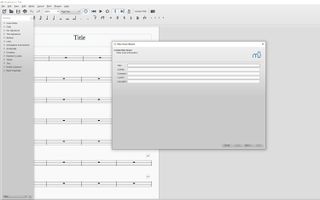

When you click on Create New Score, you'll get a wizard to walk you through the basics, including the title and composer. The next screen is more important, because it's where MuseScore will ask what kind of piece you want to compose. There are 20-odd templates, with everything from a bluegrass band, to a string quartet, to a full orchestra.

Drawing on the theme to Star Trek: The Next Generation as an inspiration, I selected the brass-quartet template. This gave me access to two trumpets, a trombone and a tuba. After I toyed around with a few notes, it didn't have the range I was looking for, so I wound up starting fresh, with a blank template. From there, I was able to select the instruments I wanted: a French horn, an oboe, a clarinet and a bassoon.

In the end, only the oboe and the bassoon made the cut. But it's easy enough to change instruments by right-clicking on a staff and then selecting the Change Instrument button under Staff Properties. My final composition included an oboe, a bassoon, a trumpet and a violin — as well as a timpani and some chimes, because I absolutely could not help myself.

Still, it's important to choose your template wisely. It's easier to start with a woodwind-quartet template and wind up adding some brass later than to start with a rock-band template and have to rewrite the entire thing.

In the wizard, you'll also pick a key signature, which is where knowing a little music theory comes in handy. If you have absolutely no idea where to start, it's always a good idea to pick C major and adjust from there. (I went with B flat major, because it sounds heroic.) Likewise, a 4/4 time signature never hurt anyone.

Now, you'll find yourself at the scariest part of the process: facing down a blank canvas.

Take notes

Before I could have my sweeping space score, I needed something much simpler: a melody. I'm not exaggerating when I say it took me as much time to work out a single melody line as it did to write all the rest of the harmony parts put together.

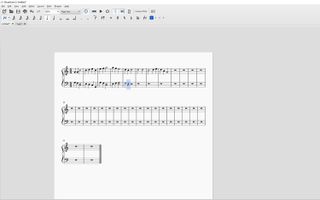

If there is a trick to creating melodies, the greatest composers of the last few hundred years have not stumbled upon it. Your best bet in MuseScore may be to press the P key to bring up a small virtual piano. You can use this to input notes or just to tool around until you find a melody you like.

The two keys I needed to know right away were N and the spacebar. N opens up notation mode, which is where you can use your keyboard (as in, your typing peripheral; if you have a musical keyboard, you can also use that, but that's kind of a separate tutorial) to input notes into a measure. The spacebar plays the music, so you can listen to what you've written and ensure it's OK before moving on.

While MuseScore has tons of options (just look at the View menu to see all the extras you can toy around with), the actual process of adding notes is deceptively simple. Press N to start editing a measure. Then, press A, B, C, D, E, F or G to add the note you want. That's it. Remember that, in the treble clef (right-hand piano, guitar, trumpet, clarinet, etc.), the bars in the staff correspond to FACE, while in the bass clef (left-hand piano, bass guitar, tuba, bassoon, etc.), they correspond to ACEG.

By default, everything will be a quarter note, but you can modify this by pressing the number keys: 4 for an eighth note, 5 for a quarter note, 6 for a half note and 7 for a whole note. If you need to add an augmentation dot (most likely for a dotted half note), press the period as well. Then, press the letter corresponding to the note, as normal.

MORE: 25 Android Apps That Are Actually Worth Paying For

If you mess up, you can press Ctrl + Z to undo your most recent action, as in most programs. Or, you can delete the errant note (Del), adjust the pitch (up or down arrows) or change the length (click on the note; then click on the desired note length in the upper-left portion of the screen). There are other, more subtle ways to add and adjust notes, but again, for going from "zero" to "workable score," this is the fastest method to learn.

Just one more thing: To write a chord instead of a single note, hit Shift after you input the first note; then press the key corresponding to the next desired note. (For example, for a C-E-G chord, hit C, Shift, E, Shift, G, in that order.)

An hour into my project, I'd written the first two measures of the melody. Another hour in, and my main motif was done: more or less a simple scale, running up and down a B flat chord. A third hour went to composing the bridge (which I eventually moved from trumpet to oboe, since it had a gentler sound). The final hour of my opening volley went into putting the whole melody together, along with a few simple placeholder percussion parts, so I could make sure everything fit rhythmically.

From there, as deceptively simple as it sounds, all I had to do was repeat the same process three or four times, making sure none of the harmonies sounded too out of place. Simple, right? Sort of.

Produce and export

Adding notes, constructing harmonies, determining rhythms and building structure are the hardest parts of writing or arranging a song, but once you know how to add notes to MuseScore, you have at least 90 percent of the tools you need at your disposal. The rest was easy enough to look up in the guidebook.

One thing that I found useful, however, was knowing how to export the music to a common format. After all, very few systems can read a MuseScore file, and it's a cumbersome way to share your creations with friends, family and potential employers.

MORE: Music Online - Streaming Radio, Tool & App Downloads - Tom's Guide

Exporting your music, be it as a PDF or an MP3, is easy enough. Just select File, then Export. Next, choose your preferred format. (I like WAV files, but they can take up a lot of space, if your piece is very long or very intricate. MP3s are good if space is an issue; MIDIs are good if you want to import it back into MuseScore or a similar program.)

There's a catch in this neat little arrangement, though: Everything you export will sound a little like a MIDI file from an early-'90s PC game. My epic intro was sounding a little more like a retro Final Fantasy credit roll. As advanced as scoring technology has become, it's still extremely difficult to replicate the sound of a real instrument without employing said real instrument.

I have yet to find a perfect solution to this problem, but the best option is to employ SF2 files. These file packages install much more realistic-sounding instruments in MuseScore, allowing you to export something that sounds — well, not 100 percent real, but at least a little more pleasing to the ear than the program's defaults.

MuseScore has instructions for downloading and installing SF2 and SFZ files (a more complicated version of the SF2 process) on its website, and even offers some of its favorite free packages. I haven't found one that I recommend above all others yet, but it's easy enough to experiment — provided you have a lot of hard-drive space. The file sizes can range from a few hundred megabytes to a few gigabytes.

Once you've downloaded and installed your chosen SF2 file, open up the MuseScore Synthesizer under the View menu. Then click Add, and select the package you'd like to try. I wound up finding an SF2 for a full orchestra that provided reasonably good versions of the oboe, bassoon, violin, timpani and chimes. The trumpet still sounded a bit like something rendered on a Sega Genesis, but it was a big step above what I started with.

The creative process

If you've never composed something before, be aware that the process takes a lot longer than you'd expect it to. Even after you get your notes on the page, you still have to determine tempo, dynamics, crescendos, fermatas and lots of other subtle touches. It's easy to adjust volume and intensity on the fly when you're playing a piano, but if you leave explicit instructions out of MuseScore, your final product will sound dull and lifeless.

As for me, at the time of writing, my players have yet to hear their theme music. It will debut at our next weekly game. (You can hear it here, though; just don't tell them yet!) And then, I'll get to experience the best part: sharing my creation with a receptive audience. Even if I have to take it back to the drawing board, at least MuseScore will give me an easy way to rework it.

Credit: MuseScore

Marshall Honorof is a senior editor for Tom's Guide, overseeing the site's coverage of gaming hardware and software. He comes from a science writing background, having studied paleomammalogy, biological anthropology, and the history of science and technology. After hours, you can find him practicing taekwondo or doing deep dives on classic sci-fi.