Resin: The Next Little Thing for 3D Printing

Alternative 3D printing tech uses a projector and photosensitive liquid to make objects that can be very detailed and very tiny.

3D printing promises to bring users' digital visions into the physical world. That's literally what happens with an alternative to the mainstream 3D tech called stereolithography (SLA). Utilizing the same kind of projector often used for PowerPoint presentations and movie nights, these devices turn liquid into finely detailed objects.

The technology garnered attention at the recent Maker Faire in New York City, with models ranging from pricey and highly polished to extreme DIY.

Typical 3D printers, such as the Cubify Cube, use a process called fused deposition modeling (FDM), in which a nozzle extrudes melted plastic filament, meticulously tracing out every detail of the object it's making. SLA printing turns the process on its head. Instead of starting with a solid raw material, it starts with a liquid and turns it solid.

MORE: 5 Coolest 3D Printers of Maker Faire 2013

The process uses a liquid, called photosensitive resin, that hardens into solid Polyester, vinyl ester epoxy or urethane when exposed to certain frequencies of light. Some resins react to visible light and have to be stored in black containers. Others react to ultraviolet light and have the same handling rule as for vampires: All's well if you keep them out of the sun.

To make the change, a Digital Light Processing (DLP) projector shines an image into a vat of resin for each layer of the object to be made. (With some modification, the projector can be tweaked to put out UV light if needed.) Once the first layer hardens onto a platform, the platform moves a tiny bit deeper into the pool of resin — and the projector shines a new image to harden the next layer.

The big benefit of SLA printing is the ability to make objects very small, very detailed or both. The resolution of the print job on an FDM printer is limited by the thickness of the plastic coming through the nozzle. Good home printers, such as the MakerBot Replicator 2, get down to 100 microns (one-tenth of a millimeter, or 0.0039 of an inch). That may sound good, but the individual layers in a print job might still be visible, and surfaces won't be totally smooth. With a resolution of 10 microns or better (depending on the resolution of the projector), resin printers produce much finer detail, and items come out smoother.

Get instant access to breaking news, the hottest reviews, great deals and helpful tips.

That makes SLA printers a good tool for jewelry makers, for example, who can design a detailed piece and use the resin print to make a mold.

MORE: Find the Best 3D Printer for You

But that precision comes at a price. Standard fused deposition modeling printers that use plastic filament can be as cheap as about $500 for a kit — full assembly required — and slightly more than $1,000 for a fully built model (though some models can be twice as much). In comparison, B9 Creator's eponymous all-metal resin printer, which emerged from Kickstarter last year, costs $2,990 for a kit or $4,995 assembled. At Maker Faire, though, one hacker was showing off a DIY model that could cost well below a grand.

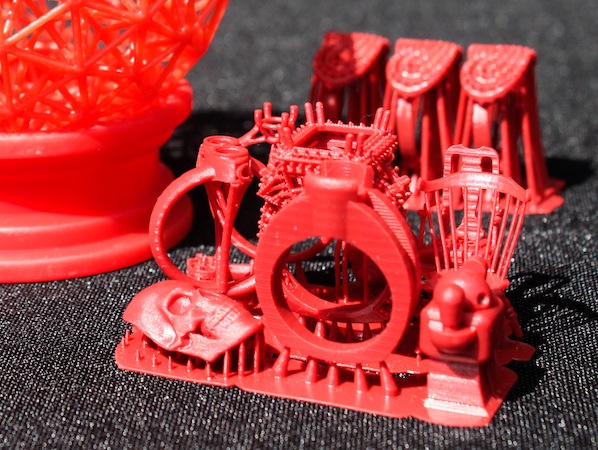

Texan Patrick Hood-Daniel, owner of buildyourcnc.com, displayed a wooden prototype that held a projector in place with a couple of bolts. The resin vat was just a small metal container. But even that rough setup turned out items that meet or beat the detail of jobs from an FDM printer, including a bowl that appeared to be woven of fine filament and a tiny Google Android figurine not much larger than a pencil eraser.

The device Hood-Daniel displayed is just and experiment. He's still mulling over offering a an actual product. Hood-Daniel said that if he does, he would aim to put together a polished kit costing about $400 — though it would require a project that could cost an extra $200 to $400.

But for now, it's a proof of concept. "I just wanted to see if it was possible," he said.

Follow Sean Captain @seancaptain. Follow us @tomsguide, on Facebook and on Google+.

Sean Captain is a freelance technology and science writer, editor and photographer. At Tom's Guide, he has reviewed cameras, including most of Sony's Alpha A6000-series mirrorless cameras, as well as other photography-related content. He has also written for Fast Company, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and Wired.

-

MallocArray And then there is: http://www.kickstarter.com/projects/117421627/the-peachy-printer-the-first-100-3d-printer-and-sc?ref=liveReply -

alidan got to love how you got the thumb down when that is one of the better if not the best printing method, only problem is the print size they went with for the 100$ version.Reply -

noob2222 while SLA printing is an easy concept, easy to implement, the cost of resin is too much.Reply

SLS 3d printing is the next big thing.

http://www.odd.org.nz/guitars.html -

alidan @noob2222Reply

it depends on the cost of the laser. sls is great and all, but required a more powerful laser than sla.

honestly, even sls wouldn't find its place in a home because of the mess it would make, however, the peachy printer just made the resin a non issue with a messes.

we will probably know next year which one will be the best, personally i am hoping for sls because the powder would make a wide WIDE range or materials a viable option for prints, and hopefully be cheaper than current markup (50$ a kilo of pls or abs, but pellets are 5$ a kilp) -

IndignantSkeptic Of course hardware that a hacker makes would be much cheaper at the same quality than other hardware. That is because the hacker's research & development and patent royalty costs would be nearly zero because they would probably just steal all the intellectual property via reverse engineering and industrial espionage.Reply -

merikafyeah Nay! The next big thing is the old, old thing. That's right, all that paper you have lying around, you can now use to make 3D stuff:Reply

http://www.techhive.com/article/2049109/this-3d-printer-uses-paper-regular-old-paper-instead-of-filament-or-resin.html

And no, if you watch the video you'll know that this isn't flimsy stuff like paper-mache, but something far more durable, resembling wood. Cost of materials is low (and freely available for most people), but the same downside for nearly every 3D printer today: the cost of the printer itself. Still out of reach for most people. But they're working on that. I have confidence that one day it'll be affordable enough. Til then, the Peachy Printer looks like a swell alternative. Hope they succeed. -

Pailin Nice link thanks MallocArray.Reply

It was a pleasure to see that guy thinking clever ways around all those little things he needed to get done!