Tom's Guide Verdict

Horror fans may enjoy it, but with a convoluted plot and clunky controls, Evil Within is mediocre at best.

Pros

- +

Detailed environmental design, good soundscape, evokes Resident Evil gameplay

Cons

- -

Not actually scary, just disgusting

- -

nonsensical plot

- -

clunky controls

- -

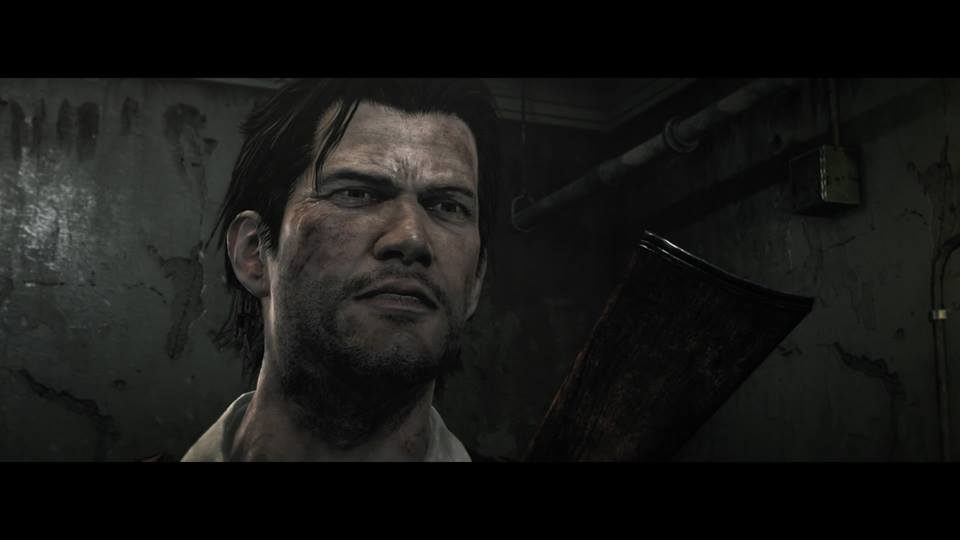

characters' faces lost in Uncanny Valley

Why you can trust Tom's Guide

A grimace is a pretty long way from a scream. But a grimace is all that the new survival horror video game Evil Within could get out of me.

The Evil Within certainly has a good horror pedigree. Its director, Shinji Mikami, also created the Resident Evil series of action-survival horror games. But in its attempts to evoke games like Resident Evil 4, Evil Within, released Oct. 14 for PlayStation 3, PlayStation 4, Xbox 360, Xbox One and PC, Evil Within ($60), draws too much on the mistakes and clichés that defined gaming 10 years ago, and not enough on the good. Such familiarity may be enjoyable to some players, but it doesn't justify the price of a newly released title.

MORE: Best Gaming Keyboards

Story

The best thing about Evil Within's story is that it's mechanically adequate. As a player, your task at any moment is clear: Escape this place, find this person, do not die. That's the most important task a video-game narrative has to achieve.

But in terms of telling an interesting, cohesive story, the game offers a jumbled mess of underdeveloped, unconnected tropes. Evil Within may claim its approach is "old school," but it's taking the worst parts of gaming circa 2000 — cinema envy, linear designs, long cutscenes — and ignoring all the progress narrative development has made in the past 15 years.

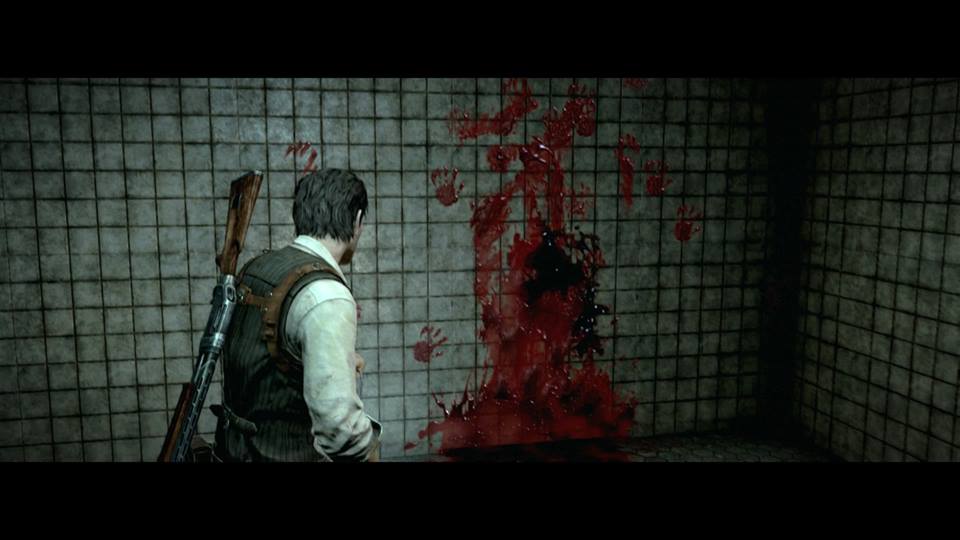

Players take the role of Sebastian Castellanos, a scruffy-faced, gruff-voiced, vest-wearing detective assigned to investigate an issue at a local mental hospital. Sebastian discovers that the hospital has become a slaughterhouse. You'll find ceilings hung with dead bodies, sewers full of blood, and a grunting, disfigured, chainsaw-wielding patient who pursues Sebastian through filthy and dilapidated rooms.

Sebastian escapes the asylum, but his surroundings continue to flicker and change in the blink of an eye, transporting him to other clichéd horror locales: a secluded forest, a Victorian-Gothic mansion, and still more hospitals, all crawling with creatures best described as demon zombies.

Eventually, Sebastian learns that he is inside the mind of a mad scientist named Ruvik, thanks to an experiment Ruvik has undertaken to unite all human consciousness. Why Ruvik wants to do this — is he perhaps just a big anime fan? — is unclear.

Horror genre

Narrative technicalities aside, the most important part of any horror game is the horror. But it's hard to figure out exactly what's scary about Evil Within. Which parts of the game were designed to inspire fear?

Over and over again, the answer is: damaged bodies. Fear of blood, wounds and physical deformities permeates the game's visuals, from the blood-soaked environments to the demon-zombies with barbed wire and shrapnel twisted into their bleeding flesh. Such "body horror" is often merely disgusting and disturbing rather than horrifying, and Evil Within is no exception. There's tension and discomfort, but no lasting or memorable frights.

This particular fear is an odd choice for a video game, where the act of playing involves an implicit understanding that actual bodies are not involved. Digitally simulated violence quickly becomes less frightening after you've died and restarted the level a few dozen times.

Even the unavoidable damage Sebastian suffers — the wound to his leg in the beginning of the game, or his impalement at the end — still has no sting, because Sebastian's surroundings aren't real, not even within the narrative. Evil Within may constantly tease you with the threat of death, dismemberment and deformation, but it won't ever commit.

But for all that, fear of damaged bodies is nowhere to be found in the actual narrative. Instead, the threat is Ruvik's plan to upload and unify all human consciousness into a single brain. Paradoxically, it's in Ruvik's disembodied virtual reality that the threat of bodily harm appears.

If Ruvik has the power to warp reality, why create a reality so entirely defined by physical pain? Perhaps the game's environments are supposed to be a metaphor for Ruvik's physical and mental trauma. But if so, this trauma is never anything other than, as the game's title suggests, "evil." This is yet another horror cliché, and an offensive one: portraying mental illness as evil, and mentally ill people as threatening monsters.

Gameplay

Evil Within plays a lot like the Resident Evil games of the past 10 years, particularly Resident Evil 4. But unlike that game's protagonist, Leon Kennedy, an action hero Sebastian is not. In Evil Within, running, shooting, punching and other controls all feel clunky and heavy. Players get the sense that they're constrained by Sebastian's own limitations, a nice echo of the game's visual obsession with bodies.

This approach would work better if Evil Within were a stealth game through and through, but it starts out as stealth and gradually becomes action. Instead of being able to choose their approaches, players get dragged along in the transition.

Evil Within is a third-person shooter, and Sebastian’s body is visible on the screen at all times. When you aim your weapon (pistol, shotgun, crossbow, etc.), the camera is fixed just behind his right shoulder. When you sneak around, Sebastian's bland behind fills the screen, particularly when you're in narrow spaces.

MORE: 15 Best Android Shooter Games

Evil Within is at its best when you have to get from one end of a big area to the other, using whatever limited equipment you can find. That's genuinely challenging and suspenseful, and the game often lets players choose among several different approaches.

There are some enemies, usually bosses or larger foes, you must either fight or run from. The only way you can tell the difference is by dying a few times, until you figure out what the game wants you to do.

Each level also contains a handful of puzzles and treasure hunts to investigate. Here the game's attempts to be old school are successful: As in older games, Evil Within offers no hand-holding. You'll have to figure out what to do just from environmental clues.

Art and graphics

For all its flaws, the environmental design in Evil Within is often very striking. The surfaces — usually some combination of dirt, flesh, rust and rough stone, are all very detailed, and the rooms and areas have been meticulously designed to look really lived-in — or, rather, died-in.

Characters' faces are less impressive; they all appear gray, stiff and waxen. Protagonist Sebastian is the one exception. His face is far more detailed and lifelike than the other characters', but it only has a single expression.

Evil Within pulls out all the stops on lighting effects, taking full advantage of so-called "next-generation" graphics engines. Simulating multiple light sources in a scene, and creating dynamic shadows as those light sources and the player character move around, are difficult, but Evil Within meets the challenge.

However, the game's textures, especially in the light, do sometimes look a little too crisp, giving the game a sort of sharp, hyperreal sheen to it. This effect is common in next-generation games, which benefit from powerful graphics engines but haven't quite mastered the nuances of real-life physics. In Evil Within, I found the hyperreality to be even more jarring than usual, as the game's premise depends on us believing that the bodies on screen are real and in danger.

Music and sound

From the haunting atmospheric music to the squelch of exploding skulls, Evil Within creates a soundscape as rich and detailed as its visual environments. Not only do the sounds increase the tension and suspense, but they also help players locate enemies, even those you can't see right away.

My favorite sound design revolves around the mirrors that transport Sebastian to a hospital that serves as the game's save points. These mirrors can be located by following the sounds of Debussy's "Clair de Lune," and the closer you get to the mirrors, the louder a creeping whine grows.

Activating the mirror makes the whine grow into a shrill note, accompanied by the sound of breaking glass. It's a strong, distinct sequence of noises that serves both to add atmosphere and to help players navigate the game world.

Bottom line

If you're really craving some Resident Evil 4-style action, Evil Within will scratch that itch. But not even the game's impressive environmental design and soundscape can save it from its own lackluster horror.

Evil Within is a mediocre game that gets away with it because all of its mistakes have been made so many times, in so many video games, that we've come to think of them as normal. We may even be nostalgic for them. Ultimately, though, the clichéd writing, clunky scares and unbalanced combat add up to an unsatisfying experience.

Specs

Publisher: Bethesda Softworks

Developer: Tango Gameworks

Genre: Survival Horror

Price: $60

Release Date: Oct. 14

Platforms: PS3, PS4, Xbox 360, Xbox One, PC

PC Requirements

OS: 64-bit Windows 7 or Windows 8/8.1

Processor: i7 or an equivalent with four plus core processor

Memory: 4 GB RAM

Graphics: GTX 460 or equivalent 1 GB VRAM card

DirectX: Version 11

Disk Space: 50 GB available space

| Our Favorite Gaming Hardware: |

| Best Gaming Mice |

| Best Gaming Desktops |

| Best Gaming Keyboards |

Jill Scharr is a staff writer for Tom's Guide, where she regularly covers security, 3D printing and video games. You can follow Jill on Twitter @JillScharr and on Google+. Follow us @tomsguide, on Facebook and on Google+.

Jill Scharr is a creative writer and narrative designer in the videogame industry. She's currently Project Lead Writer at the games studio Harebrained Schemes, and has also worked at Bungie. Prior to that she worked as a Staff Writer for Tom's Guide, covering video games, online security, 3D printing and tech innovation among many subjects.

-

turkey3_scratch No surprise, probably a game that focuses on everything on graphics resulting in poor gameplay and a deceitful game overall.Reply -

Samantha Mcdoograh I think no matter what horror game comes out people find a reason to bitch about it. I am currently playing the game and find it creepy and entertaining. Lighten up people.Reply -

JeckeL Reply14555996 said:I think no matter what horror game comes out people find a reason to bitch about it. I am currently playing the game and find it creepy and entertaining. Lighten up people.

Yea I've found that with horror games (much like horror films) it depends on what state of mind you're in when viewing/playing. If you go in completely immersed, lights off, no background noise, focused on the game or the film, you'll get a lot more out of the experience than if you go into it intending on reviewing the game on a scale from 1/10 and reporting your findings to the citizens of the internet. It's like when you get a group of friends together in a living room watching a horror film with the lights on chances are you'll be talking to your buddies and joking around the whole time and be completely disengaged from the experience. If you watched it alone, lights off, no one around, right in front of the TV, it'd be MUCH more frightening

Take the original dead space for example. For me, it's one of my favorite games of all time... but if I were reviewing it using the standard criteria (i.e. gameplay, story, etc) I'd give it a 6/10 at most. The combat is slow & sluggish, level design is pretty much the same throughout, etc... this is the flaw with reviewing games, do you give an opinion based on your experience with the game and how it made you feel personally, or review the game factually using scales and measurements -

Jill Scharr Hi JeckeL, this is Jill, the writer of this piece. I think you're really right about the fact that there are two approaches to reviewing something: how a game made you feel personally versus how the game stacks up against "standard criteria." I think an interesting review balances both approaches. For example, last month I gave Hyrule Warriors a 3.5 out of 5 even though I love it, because I was balancing my genuine enjoyment of the game with the game's own limitations according to "standard criteria." With Evil Within, it was kind of the opposite--my personal experience of the game was largely negative. I didn't like the overdependence on gore and jump scares, and a story as jumbled as Evil Within's is enough to turn me off of a game. But by using the "standard criteria" I can tell you that Evil Within does do some things really well, like environmental and sound design, and creating something close to a Resident Evil feeling. That's how I arrived at the score I did.Reply