How Disney killed the most interesting thing about Star Wars

Star Wars is worse without the messy, wonderful Expanded Universe

Here at Tom’s Guide our expert editors are committed to bringing you the best news, reviews and guides to help you stay informed and ahead of the curve!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Tom's Guide Daily

Sign up to get the latest updates on all of your favorite content! From cutting-edge tech news and the hottest streaming buzz to unbeatable deals on the best products and in-depth reviews, we’ve got you covered.

Weekly on Thursday

Tom's AI Guide

Be AI savvy with your weekly newsletter summing up all the biggest AI news you need to know. Plus, analysis from our AI editor and tips on how to use the latest AI tools!

Weekly on Friday

Tom's iGuide

Unlock the vast world of Apple news straight to your inbox. With coverage on everything from exciting product launches to essential software updates, this is your go-to source for the latest updates on all the best Apple content.

Weekly on Monday

Tom's Streaming Guide

Our weekly newsletter is expertly crafted to immerse you in the world of streaming. Stay updated on the latest releases and our top recommendations across your favorite streaming platforms.

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker is in theaters at last. Forty-two years and nine mainline movies after Star Wars debuted, the Skywalker saga has come to a close. And the fan reaction is pretty mixed. At best, The Rise of Skywalker seems like the kind of thing you can enjoy just because it presents so many familiar Star Wars trappings; at worst, it's a once-mighty series limping over a finish line.

Whatever the case, I don't think the problem is with The Rise of Skywalker itself. The problem isn't with Rian Johnson's subversive The Last Jedi; it isn't with J.J. Abrams' predictable The Force Awakens. The problem isn't with Rogue One, Solo, The Mandalorian or any of the various spinoffs.

The problem, I think, is with Disney — and the fact that Disney truly, madly, deeply does not understand Star Wars — except as a way to print money in perpetuity. The House of Mouse saw something popular and snatched it up, without ever stopping to think about why people loved it so much in the first place. All Disney wanted to do was give fans more of what they wanted.

But Star Wars has always been a stronger series when it ignored fan expectations and did its own thing. And in order to understand why, it's time to revisit the much-beloved, much-maligned Expanded Universe.

This piece isn't going to be an exhaustive defense of the Expanded Universe or a comprehensive breakdown of everywhere the Disney films went wrong. Those articles are already out there, and frankly, those subjects are all matters of taste. Either you liked the EU or you didn't, and likewise with Episodes VII, VIII and IX. But to understand why Star Wars feels so bland now — and why it never did before, even during a long hiatus from the big screen — it's necessary to see another way the story could have gone.

Your first step into a larger world

To be clear, I'm not saying that Star Wars was ever some kind of high-minded art project for the betterment of humankind. Disney was only capitalizing on what was already there, both in terms of story and franchise structure. George Lucas pretty much invented the "summer blockbuster with merchandise" model that has carried Hollywood from 1977 into the modern day. One aspect of that merchandise is tie-in media.

Star Wars wasn't the only sci-fi franchise to have tie-in books, comics, video games and tabletop adventures. But what's interesting about Star Wars is how all of its tie-ins tried to maintain some internal consistency. From "Splinter of the Mind's Eye" (Del Rey, 1978) and the Marvel comic series in the late '70s all the way up to "Crucible" (Del Rey, 2013) and the Star Wars: The Old Republic MMO in the mid-2010s, almost every single Star Wars story on page and screen was part of the same continuity. Authors, fans and corporate types alike dubbed this project the Expanded Universe.

Get instant access to breaking news, the hottest reviews, great deals and helpful tips.

Compare and contrast that to a franchise like Star Trek, which has just as many (and possibly more) comics, books and games associated with it. Star Trek makes it very clear that only what you see in the TV shows and films is "canon." That stuff "really happened," whereas all of the tie-in media is just a "what-if" story. If it fits into the existing franchise, great; if something on screen contradicts it later, too bad. This is a cleaner, albeit less satisfying way of managing things.

There have been whole online volumes written about how to measure the "canonicity" of the EU — Lucas himself said that he believed all those stories took place in a "parallel universe" — but the point is, to many fans, the novels, comics and games were as real as the movies themselves. These media weren't just a way to pass the time between films; they were legitimate continuations of character and story arcs that we didn't see come to fruition on screen.

As such, I would argue that fans who connected with Star Wars through the Expanded Universe did so in a way that's fundamentally different from how fans who only saw the films interacted with that world. To movie fans, Star Wars comprised three (and later six) movies and basically nothing else. The movies occupied a paramount position in these fans' minds; after all, there was really nothing else to Star Wars.

However, fans who embraced the EU had a very different interpretation of the franchise. The movies were still arguably the most important part of the equation, but they were only six cornerstones in a much, much larger setting. In fact, in terms of sheer volume, the movies weren't all that substantial. Twelve hours on screen is not much when weighed against thousands upon thousands of pages of pulpy printed adventures and hundreds of hours played on PCs and consoles.

Keep the distinction between these two kinds of fans in mind, and why Disney might be interested in it. If your version of Star Wars includes hundreds of stories, a bad one here and there is par for the course. But if your version of Star Wars contains only six movies and nothing else, a bad entry could be what turns you off of the series forever.

A brief history of a fictional universe

If there's one thing I want to convey in this piece, it's just how big the Expanded Universe was. It's nearly impossible to count all the comics and video games, but there were 156 adult novels. That's not counting young adult (YA) and children's novels, tabletop RPG rule books, technical manuals, official magazine articles, online novellas, and a bevy of other printed materials that defy easy categorization.

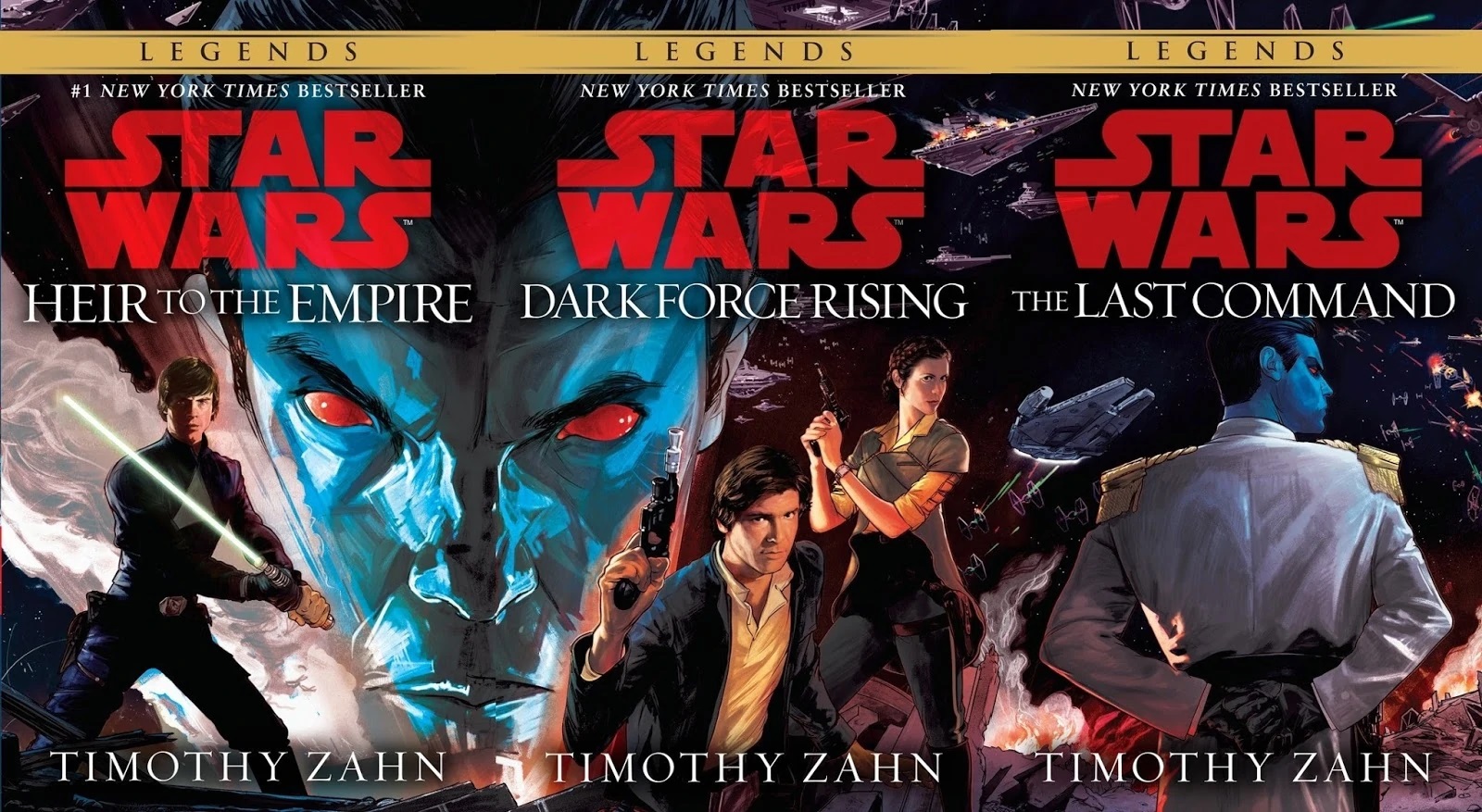

Between 1983 (Return of the Jedi) and 1991, Star Wars was more or less a dormant property. But then, Lucasfilm gave sci-fi writer Timothy Zahn license to write his very own post-ROTJ novel trilogy. The result was "Heir to the Empire," (Bantam Spectra, 1991) a sci-fi action-adventure story that recaptured a lot of the original magic of the films while advancing each individual character's arc. You may have heard fans (correctly) whining about how Grand Adm. Thrawn would have been a better villain for the Disney trilogy; this is where he came from.

From 1991 through 1999, the Star Wars universe got very weird — and very fun. Lucasfilm and publisher Bantam Spectra contracted inventive sci-fi writers, up to and including the legendary Vonda McIntyre, to pad out the timeline after Return of the Jedi. To be clear, we had some Luke, Han and Leia adventures of the week. But we also had a series all about X-wing fighter pilots and a whole YA offshoot about the next generation of Jedi knights.

We learned about Mara Jade, who served the emperor and made it her life's work to assassinate Luke — before falling in love with him. We had a first-person account of rebuilding the Jedi Order from Force-sensitive fighter pilot Corran Horn. And we got to see Leia's ascent from freedom fighter to president of the fledgling New Republic.

What was incredible about these books isn't necessarily that each one was a masterpiece. In fact, only a handful were anything beyond ordinary sci-fi beach reading — and some were real clunkers. (Don't read "Planet of Twilight" [Bantam Spectra, 1997]. Just don't.) But each author brought new sensibilities, new characters and new technologies to the Star Wars universe. Supporting characters persisted from book to book, taking on new roles under different authors. The universe suddenly felt much bigger than three Rebels and their sidekicks.

The Expanded Universe asked, "What does Star Wars look like without its main villains? What does Star Wars look like without its central cast?" And the result was pretty fascinating. What's more, because each story came from a different author and there was no long-term "plan," there was no consideration for fan theories or satisfying an audience beyond giving them a good story. The EU was a big, messy place where stories grew organically. A lot of it didn't work. But they often failed because they were experimental, and even the bad ones were interesting.

Even when Bantam Spectra handed the license over to Del Rey and Lucasfilm became more involved, the experimental streak didn't end right away. That was the beginning of the controversial "New Jedi Order" series, in which the heroes fought against a race of extragalactic invaders called the Yuuzhan Vong. Armed with organic biotechnology and a resistance to the Force, the Vong seemed tailor-made to counteract the Jedi. The resulting 19 books changed a lot about the Star Wars universe, from killing off major characters to establishing whole new government paradigms.

Whatever else you can say about the EU, it was bold and it was different. And that's something Disney simply doesn't want.

The House of Mouse

After Disney purchased the Star Wars license in 2012, it was only a matter of time until the company decided to nix the Expanded Universe. On April 25, 2014, the Disneyfied Lucasfilm staff wrote a blog post explaining that the EU would be decanonized and printed under a "Legends" banner from now on. The message was clear: With new films on the way, Disney couldn't have nearly 40 years of semiofficial existing material cluttering up the mythos.

And I get that. Who doesn't? You can't invite filmmakers onto an exciting new Star Wars project, then tell them, "By the way, this had better not step on the toes of any of our thousands of existing stories." No, if we wanted new films, the EU had to go. While I would have preferred to keep it, the only other solution would have been to do a Star Trek reboot-style time-travel story. And Star Wars has never really been interested in those.

The problem is that Disney has approached Star Wars with a fundamentally different mindset from that of the creators who made the EU so special. The books wanted to move the story forward in unexpected ways; the comics and games wanted to explore hidden corners of the galaxy that we may never have seen otherwise.

But when Episode VII debuted, all we got was a beat-by-beat rehash of Episode IV, with three brand-new protagonists struggling to share screen time with a bunch of recurring characters. The Empire was back, with a different name. The Rebels were back, with a different name. The story, themes and structure were all the same as before. For fans who had grown up with the weird tapestry of the Expanded Universe, how could that fail to seem a little disappointing?

The Last Jedi got a little closer to the experimental nature of the EU, but it didn't stick the landing. The movie brought up some excellent, subversive points: Have the Jedi done more harm than good? Are the Rebels and Empire, in some form, doomed to repeat a cycle forever? Did making Luke, Leia and Han into mythic heroes deny them their own humanity? These were questions that some of the books had dealt with, too, to great effect.

But then, the interviews came out, and it seemed like J.J. Abrams would deliver fans exactly what (he thought) they wanted in The Rise of Skywalker: a definitive ending that doesn't question too many assumptions about the Star Wars universe. Disney, Abrams and many of the fans, it seems, want the same thing: a safe, predictable, intensely curated Star Wars canon, where every film, book, comic and game comes tightly scripted and utterly in line with a kind of overarching vision. If there's room for spontaneity in such an arrangement, it's hard to see it.

Legends never die

When the first trailer for The Force Awakens dropped, fans took to YouTube in the hundreds to record their reaction videos. When people saw the Millennium Falcon, they grinned. They cheered. They cried. They thought that something they would never see again was finally, finally back at last.

But my question to them is, where were you all this time? Star Wars never went away. Like the Force, it was all around you. You wanted to see Luke become a Jedi Master and start his own academy? You wanted to see Han and Leia raise a family? You wanted to see a whole new cast of characters go on adventures in unexplored regions of the galaxy? All of that happened. The stories were always there.

This isn't calling anyone's fan credentials into question. Folks who encountered only the movies are Star Wars fans just as legitimately as are folks who read every single book. But if Star Wars meant so much to you, why didn't you want anything to do with it outside of a movie theater?

In "Outbound Flight," (Del Rey, 2006) the New Republic sends two Jedi out beyond the edge of the galaxy on a mission of discovery. They encounter an alien civilization that rivals the Old Republic in scope and learn that even Jedi training may not prepare unwary travelers for what they find in the distant corners of the galaxy.

In "Traitor," (Del Rey, 2002) Han and Leia's eldest son, Jacen, must survive as a prisoner of war aboard a Yuuzhan Vong ship. There, he learns to question every assumption he ever had about the Jedi. He must also team up with an arrogant, second-rate Jedi Knight and a morally gray Jedi Master to escape. The cast has five important characters. None of them are from the movies.

In the game Knights of the Old Republic II, a Jedi Knight, traumatized by a catastrophic war crime, cuts himself off from the Force entirely, only to find that three Sith Lords seek the power he's unwittingly discovered. One of them trains him but has no stake in whether he veers toward the light or dark side. She has seen through the dichotomy and realizes that the Force itself is a kind of crime against free will.

I can't imagine Disney doing any of this, because what's Star Wars without scrappy rebels against a fascist empire? Disney doesn't want to know. The EU did.

Bottom line

To be crystal clear, there's nothing inherently malicious or even cynical on Disney's part here. All the company wants to do is give fans something they'll love — but that comes with its own set of shackles. If you want to please a group as large and diverse as Star Wars fans, ultimately, all you can offer them is a middle ground. You have to be familiar and reinforce the things that people loved about three films from four decades ago, or else the audience will feel alienated. And if there's one thing Disney does not do, it's alienate its fans.

Remember, though, that Episode IV itself was a profoundly weird movie. There was nothing else like it. The prequels, too, for all their faults, didn't go the way that anyone expected them to. The Expanded Universe didn't care about fan expectations or wrapping everything up neatly or going viral with a memeable character. And in that, it felt more like Star Wars than the Disney films ever could.

Marshall Honorof was a senior editor for Tom's Guide, overseeing the site's coverage of gaming hardware and software. He comes from a science writing background, having studied paleomammalogy, biological anthropology, and the history of science and technology. After hours, you can find him practicing taekwondo or doing deep dives on classic sci-fi.

Club Benefits

Club Benefits