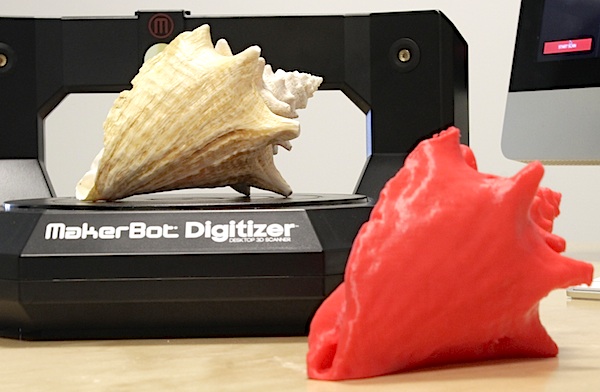

MakerBot 3D Scanner: 12 Minutes from Physical to Virtual

Dual lasers, 1,600 photographs and serious processing digitize an object in about 12 minutes for 3D printing or even adding to a video game.

The MakerBot 3D scanner doesn't look like much — an 8-inch turntable with a rectangular plastic bracket behind it. You might even wonder if some parts are missing from the $1400 device, which is available to order today for delivery early next month. But that trim design belies the device's complexity. And the one-button operation does nothing to show off the sophisticated inner workings of the software. "We've taken the time to get the software right and make it easy for people," said MakerBot CEO Bre Pettis at the scanner's public unveiling.

To appreciate the Digitizer, compare it to other devices. At the higher end, professional scanners can sell for tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars. At the lower end are apps, some fueled on Kickstarter, that use smartphone cameras or Microsoft Kinect depth cameras to stitch images together into — at best — a very rough approximation of the real-life object. In either case, the 3D scans require hours of polishing up in modeling software before the objects are printable.

MORE: 10 Amazing 3D Printed Artworks

On the Digitizer, the process takes about 12 minutes. And pressing one extra button sends the scan to a printer that can churn out near-perfect copies. The combination of scanner and printer is more than just a 3D photocopier, though. Once an object is digital, you can make any changes to it that you like.

To test it out, MakerBot uploaded a scan of the garden gnome statue that's become the mascot for the company's scanner advertisements, and asked people to make improvements. One person added a top hat, another made the beard bigger, but the winner created an entire chess-set of players derived from the gnome.

That's just for kicks, but the project shows what a simple scanning device can do. For years, 3D-print enthusiasts have told people that they can make replacements for doorknobs, broken parts of vacuums or other household items. But that assumes the average user knows enough about computer aided design (CAD) software to create these items from scratch. With the digitizer, that CAD step is removed.

MORE: 10 Great 3D-Printing Projects

Get instant access to breaking news, the hottest reviews, great deals and helpful tips.

Furthermore, the scans might never get printed. They could go form the basis of video game characters or other objects in 3D animations.

It sounds so simple, but let's look at what's really going on:

In the roughly 12 minutes after you press the button on the Digitizer's Mac, Windows or Linux software, the 8-inch turntable methodically rotates in 800 mini steps. All the while, a red laser shines a half-millimeter thick line down a slice of the shell. For each step, a camera snaps a photo of the red line, capturing all its contours. Then the process starts all over again with another laser firing from a different angle.

MakerBot's software takes these two scans and meshes them together, correcting for any errors and filling in blank spots to produce what's called a "watertight" model — one without holes, a requirement for 3D printing.

"Many of the 3D models that you see in videogames look great on the screen, but would never 3D print, because there are holes in them," said Pettis. Comprised of roughly 200,000 polygons, the Digitizer's scans compete with the most complex characters and objects that you see in AAA videogames like "Grand Theft Auto V."

Is the Digitizer for everyone? Not the way a Galaxy S4 or Xbox is. Pettis said he expects to sell tens of thousands of Digitizers. Many will go to professional designers and engineers for making prototypes, he said. But he definitely sees hobbyists joining in. "We launched this so that professionals can use it, and we made it affordable for everybody else," said Pettis.

Follow Sean Captain @seancaptain. Follow us @tomsguide, on Facebook and on Google+.

Note: An earlier version of this article made an innacurate comparison between the polygon count of a Digitizer scan and that of videogame objects.

Sean Captain is a freelance technology and science writer, editor and photographer. At Tom's Guide, he has reviewed cameras, including most of Sony's Alpha A6000-series mirrorless cameras, as well as other photography-related content. He has also written for Fast Company, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and Wired.

-

MajinCry Bwahaha! Nintendo 64 characters had, what, 150 polygons at most?Reply

GTA V probably has 1000-2000 polygons for each character at maximum detail.

Talk about false marketing -_- -

Jess Castro Majin im pretty sure that current consoles peaked around 10,000 polys as the gold standard for a character. The new gen is supposed to support up to 100,000, at least this is what I recall hearing in passing.Reply -

IndignantSkeptic MajinCryReply

I think you are off by about 10 times with the GTA 5 characters. But I think what you said applies to the previous console generation GTA games. -

Tanquen Yea, Tomb Rader 2013 looks really good and Lara is said to be around 30,000 polys . Around 40,000 with guns and other equipment on. I can’t see 100,000 or 200,000 even needed for some time until you just have so much GPU power you just don’t care.Reply -

redacid999 I never saw a seashell that looked like that on the N64!Reply

The N64 could do 150,000 polygons per *second*, so at 30fps your down to 5,000 polygons per frame. You'd end up with a couple hundred polygons per model, not 200,000 like this article suggests. -

alidan @IndignantSkepticReply

where did it talk about N64?

@MajinCry

depends on the distance away, main characters are between 10 and 20k pollys, background, depending on importance are 14k and lower, and stand ins are just good enough and have different distances where they are less pollys. a full screen on a ps3 or 360 may be at most 500k pollys. and on the pc, crysis was the last one that i heard bragging about pollies with some scenes taking up 4.6 million.

@Jess Castro

no... just no... they are upping the gold standard to about 25-40k pollies, but 100k is just asinine, at least when you understand the detail you would get out of that many pollies, how little people would notice that detail, and how it would be better to just increase the texture detail and bake the details.

@IndignantSkeptic

previous gen gta games, that may even be generous... gta was known for scale, not graphical power or beauty.

@Tanquen

i wont doubt there is a cutscene lara model with lots of pollies, but at least on the consoles i cant see a 30-40 polly main character being worth the polly investment.

NOW with that all said, this thing is over priced crap.

http://www.3ders.org/articles/20130908-rubicon-3d-scanner-on-indiegogo.html

basicly the same thing and higher quality, but lower price because they are gouging the consumer.