What Is Net Neutrality?

The FCC, courts, politicians and major tech companies are fighting over how you will access the Internet in the future. Here's what you need to know.

Here at Tom’s Guide our expert editors are committed to bringing you the best news, reviews and guides to help you stay informed and ahead of the curve!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Tom's Guide Daily

Sign up to get the latest updates on all of your favorite content! From cutting-edge tech news and the hottest streaming buzz to unbeatable deals on the best products and in-depth reviews, we’ve got you covered.

Weekly on Thursday

Tom's AI Guide

Be AI savvy with your weekly newsletter summing up all the biggest AI news you need to know. Plus, analysis from our AI editor and tips on how to use the latest AI tools!

Weekly on Friday

Tom's iGuide

Unlock the vast world of Apple news straight to your inbox. With coverage on everything from exciting product launches to essential software updates, this is your go-to source for the latest updates on all the best Apple content.

Weekly on Monday

Tom's Streaming Guide

Our weekly newsletter is expertly crafted to immerse you in the world of streaming. Stay updated on the latest releases and our top recommendations across your favorite streaming platforms.

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

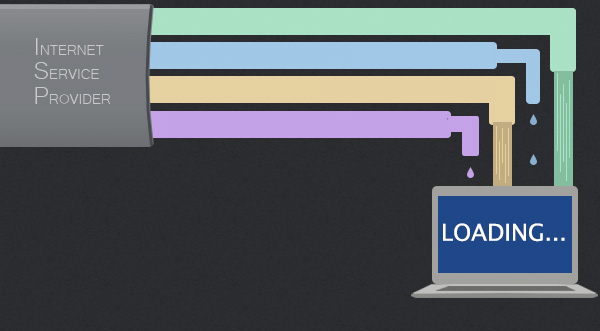

Net neutrality has gone from an esoteric concept to a headline-topper in the United States. The rise of data-intensive streaming media services such as Netflix and Amazon Prime Video and the concentration of power in large internet service providers (ISPs) such as Comcast and Verizon have raised questions about how internet access will be parceled out and paid for among content providers and consumers. An upcoming vote by the FCC to remove current net neutrality protections has thrust the subject back into the national spotlight.

Net-neutrality concerns span issues ranging from "When will my Netflix stop buffering?" to "Will the internet remain an egalitarian, democratic environment?" Let's see what the ISPs seek to do, and how the changes could affect you.

What is net neutrality?

At its core, net neutrality is about treating all content on the internet equally. This means that big content providers such as Netflix and Amazon won't be given preferential treatment by ISPs in relation to any other company, organization or individual , no matter how small.

But strictly enforcing net neutrality might also lead to inconveniences — such as slower, stuttery video-conferencing and worse cellphone voice services. Telecommunication companies worry that the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) will get all up in their business, even on basic engineering decisions. Political conservatives (including FCC Chairman Ajit Pai) have the same worries.

MORE: Could Net Neutrality Ruin the Internet?

Why is net neutrality in the news?

The FCC, under chairman Ajit Pai, has voted to remove net neutrality protections and stop regulating the internet as a utility. This is likely to be reviewed by Congress and taken to court. This provides more ISPs the opportunity to throttle users, censor content or enable fast lanes, though we've yet to see if this will come to be.

Once President Donald Trump named Pai chairman of the FCC in January 2017, the future of the open internet was in doubt. Pai has voted against net neutrality several times in his career, and many saw his appointment as the administration taking the same stance. But the debate goes back further than that.

The first event was a U.S. Court of Appeals decision in January 2014 involving a lawsuit brought by Verizon against the FCC.

The court ruled that the FCC had used the wrong piece of legislation to enforce its net neutrality policy: Sec. 706 of the Telecommunications Act of 1996, which gives the FCC the mandate to promote broadband. Instead, the court said, the FCC would need to use Title II of the Communications Act of 1934 (see more on that below), which would allow the FCC to regulate ISPs as public utilities, similar to the way telephone companies are regulated. This is what former FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler ultimately decided to do in 2015

But in May 2017, the FCC and newly appointed Trump-appointed Chairman Pai released a proposal to reverse Wheeler’s decision. You can read the proposed rules, entitled “Restoring Internet Freedom,” here. The document recommends rolling back Title II regulations on the internet, removing any legal authority the government might have to enforce net neutrality and questioning what should be done instead.

“We propose not to adopt any alternatives to the Internet conduct rule, and we seek comment on this proposal,” it reads.

On July 12, 2017, five days prior to the close of the public-comment period on Pai's proposal, dozens of potentially affected companies -- including Reddit, Amazon, Kickstarter, OkCupid, Dropbox and Imgur -- as well as the Electronic Frontier Foundation and other activist groups, held a “Day of Action,” to protest the potential abandonment of net neutrality with blog posts and pop-ups showing what could happen to the internet if net neutrality rules weren’t implemented.

But in November, the FCC announced that it would vote to end net neutrality rules altogether.

“Under my proposal, the federal government will stop micromanaging the internet,” Pai said in a statement. “Instead, the FCC would simply require internet service providers to be transparent about their practices so that consumers can buy the service plan that’s best for them and entrepreneurs and other small businesses can have the technical information they need to innovate.”

Get instant access to breaking news, the hottest reviews, great deals and helpful tips.

What is Title II of the Communications Act of 1934?

The Communications Act of 1934 is landmark legislation that, among other things, established the FCC and its authority to regulate telecom companies.

Title II of the act defines a type of company called a common carrier as, among other things, "any person engaged as a common carrier for hire, in interstate or foreign communication by wire or radio." (Under U.S. law, a company is generally treated as a person.)

Title II provides sweeping regulatory control over common carriers in Sec 202 (a). It's wordy, but worth a read.

"It shall be unlawful for any common carrier to make any unjust or unreasonable discrimination in charges, practices, classifications, regulations, facilities or services for or in connection with like communication service, directly or indirectly, by any means or device, or to make or give any undue or unreasonable preference or advantage to any particular person, class of persons or locality, or to subject any particular person, class of persons or locality to any undue or unreasonable prejudice or disadvantage."

The gist: Anyone providing a communication service can't discriminate against, or show favor toward, any of its customers. The FCC chose to classify voice telephone service as a common carrier, which has allowed it to tightly regulate providers. But in 1980, the FCC chose to classify the transmission of data as "enhanced services" or "information services," not subject to Title II.

These distinctions were made long before anything resembling today's internet. Cable TV companies, which don't have the same heritage as telephone providers, were never considered for any common-carrier designation. Many of the first ISPs were, and still are, cable companies, whose primary business is to charge both ends of the connection -- cable channels such as ESPN, and cable customers like you and me -- for access to the lines in between.

Later, the FCC ruled that wireless data providers, are not common carriers, either. The issue of whether data and the internet are public utilities is central to the entire debate.

What are internet fast lanes?

Wheeler started out far from this position on Title II. He still insisted that the twice-defeated Section 706 rationale could be the basis of a new policy. A draft net-neutrality proposal, passed by the FCC on May 15, 2014 (three commissioners voted for the proposal, and two against), would have prohibited broadband providers from deliberately slowing (or "throttling") internet traffic or blocking legal content. But it was vague on the concept of "fast lanes." The upshot was that ISPs wouldn't be allowed to slow down internet traffic, but in exchange for higher payments from content providers, they might be able to speed it up. Critics argued that creating fast lanes by definition relegated all other traffic to slow lanes.

MORE: 5 Freedoms You'll Lose Without Net Neutrality (Op-Ed)

Wheeler, however, insisted that he did not intend to allow the creation of fast lanes. In a statement on the FCC blog, Wheeler promised that "ISPs may not act in a commercially unreasonable manner to harm the Internet, including favoring the traffic from an affiliated entity."

The current proposal under Pai removes any regulation and suggests fast lanes are nothing to worry about. In fact, it assumes that ISPs will not engage in the practice at all.

“The ban on paid prioritization did not exist prior to the Title II Order and even then the record evidence confirmed that no such rule was needed since several large internet service providers made it clear that that they did not engage in paid prioritization and had no plans to do so,” it reads. “We seek comment on the continued need for such a rule and our authority to retain it.”

Fast lanes already exist, technically speaking. Content delivery networks (CDNs) are privately operated short cuts around the regular internet that shunt content, such as website data or media streams, rapidly and directly from content providers to localized servers spread out across the U.S. and the world. From each of those servers, the content can quickly hop to a nearby ISP and its customers in that area. Using CDNs and their dedicated lines is more efficient than depending on the regular internet to distribute high-bandwidth data. Most internet-based companies with enough infrastructure and resources pay to use a CDN.

Whether CDNs would be affected by net-neutrality regulation depends on the language of the regulation, but using a CDN is arguably not detrimental to the internet in the way that having to pay an ISP for preferential treatment might be.

Who is Ajit Pai?

Pai is the current chairman of the Federal Communications Commission , picked for the job by Trump in January 2017. Prior to holding that role, he served as a Republican FCC commissioner. He was appointed as a commissioner by President Barack Obama under recommendation from then-Senate Minority Leader (now Majority Leader) Mitch McConnell. (By custom, the FCC has two Republican and two Democratic commissioners, and a chairman from the current president's party serves as the fifth commissioner.)

In 2001, Pai left a job at the Justice Department to work for Verizon Communications as associate general counsel. He left the job in 2003. In 2015, as a commissioner, he voted against Wheeler’s proposal to regulate the internet under Title II.

Right now, Pai is flanked by one Republican commissioner, Michael O’Rielly, and one Democrat, Mignon Clyburn. Trump has nominated Jessica Rosenworcel, a Democrat who served on the commission under Obama, to rejoin the commission, but her appointment has to be approved by the Senate.

Pai is the first Indian American to hold the position of FCC chairman.

What does Trump say about net neutrality?

Trump hasn’t said much about net neutrality and the open internet. But in 2014, he tweeted that Wheeler’s decision was a “power grab” that Trump blamed on Obama. Trump also referred to net neutrality as a digital “Fairness Doctrine,” referring to the former FCC rule that required broadcasters to balance each piece of political commentary with an opposing point of view. The abolition of the Fairness Doctrine in 1987 allowed conservative talk radio to flourish.

While Trump hasn’t said much more on the topic, his press secretary, Sean Spicer, said in March that Trump would reverse the “overreach” and called it an example of “bureaucrats in Washington… picking winners and losers.”

Who supports net neutrality regulation?

Supporters of net neutrality regulations include consumer advocates, human-rights groups and many tech companies and organizations. The nonprofit Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) is a vocal supporter of net neutrality, as are smaller organizations such as Fight for the Future and Freepress.

On May 7, 2014, more than 130 high-profile technology companies submitted an open letter to the FCC commissioners stating their support for an open Internet. Amazon, eBay, Facebook, Google, Microsoft, Netflix, Reddit, Twitter and Yahoo all threw their weight behind the letter, along with other signatories ranging from BitTorrent to Mozilla. Many more companies have joined the effort leading up to the FCC's Feb. 26 vote on common carrier regulation.

On the July 12, 2017 Day of Action, dozens of websites and organizations -- including the ACLU, GitHub, OkCupid, Amazon, Etsy, Vimeo, Mozilla and the EFF -- banded together again.

Who is against net neutrality regulation?

Internet service providers — like Verizon, AT&T and Comcast — are the main opponents of net-neutrality regulations. ISPs are seeing a large increase in network usage as more streaming content becomes available online.

Without net-neutrality regulations, ISPs argue, they would not have the power to create a better experience for users of certain services, by finding ways to cover the cost of the additional bandwidth usage. The ISPs would also like to prioritize traffic based on how sensitive packets are to delay. Slowing down an email by a few milliseconds, for example, wouldn't be noticeable, but it would be for data packets in a videoconference.

MORE: Decoded: Net Neutrality and the 'New' Broadband

Comcast, for example, is one of several ISPs to make a deal with Netflix to improve the video-streaming experience for Comcast subscribers. Netflix is now paying Comcast to have direct access to Comcast's network, which resulted in a 65 percent speed increase between January 2014 (before the deal was in place) and April 2014, according to Netflix. In a public statement in November 2014, Comcast has said that it supports net neutrality and the specific goals the President spelled out - but not enforcement under Title II.

How does net neutrality affect Netflix?

As Netflix's popularity grows, the amount of data sent to users via ISPs also increases. During prime time, Netflix traffic accounts for roughly 30 percent of all internet traffic, with YouTube in second place at roughly 20 percent, according to a November 2013 report by Canadian internet-monitoring firm Sandvine. This puts extra strain on the ISPs, and many users have complained that streaming speed has been negatively affected. ISPs have denied intentionally slowing Netflix traffic.

In a landmark decision, Netflix has agreed to pay Comcast to ensure smooth Internet streaming services to Comcast subscribers. This deal is already impacting streaming quality for Netflix customers using Comcast, who have seen a 65 percent speed increase between January and April 2014, according to Netflix.

Tom's Guide upgrades your life by helping you decide what products to buy, finding the best deals and showing you how to get the most out of them and solving problems as they arise. Tom's Guide is here to help you accomplish your goals, find great products without the hassle, get the best deals, discover things others don’t want you to know and save time when problems arise. Visit the About Tom's Guide page for more information and to find out how we test products.

-

skit75 It is that small, still twitching, meatlump in the rear-view mirror just past the Netflix speed-bump we just ran over.Reply -

Onus Follow the money. Sooner or later, the "right" parasites will have been paid, and Net Neutrality will die. After all, they can't have the sheeple getting unfettered access to uncontrolled (i.e. unbiased) alternate news sources, but they need a way to get around First Amendment protections on freedom of speech and of the press.Reply

-

skit75 I know I get a monthly internet bill. I am pretty sure Netflix also gets a monthly/quarterly bill. So how does the ISP get to double-dip my content provider for even more money after we have both payed our bill for this traffic? I've never quite understood that part of the equation.Reply -

Krisk7 "Arguing against net neutrality are ISPs, which want the power to charge additional rates to users or companies that use an increasingly large amount of data. Net neutrality hinders the ability to respond to market demand and inhibits the ability to capitalize on new and highly profitable revenue streams, they say. Partnering with large content providers, or charging users a premium to access certain content, would bring in significant amounts of money and give content providers the ability to ensure a minimum level of quality to their users, the ISPs say."Reply

So in other words: we don't care that you already payed for the bandwith dear customer. We will be constrolling your traffic and charging not only you, but also the web services you visit. The ISPs are not even trying to hide they do it for money, they will then use to buy other ISPs, reduce competition and ask us (customers) to pay even more. -

thundervore This clip from Tek Syndicate pretty much covers it.Reply

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tb0ylZHHY08 -

house70 Don't think for a second that the increased fee for fast lane will be supported by any corporation. No, it will go full circle and hit the consumer right in the pockets.Reply

Just hope and pray to the Internet Gods that we won't have to pay once the ISP for allowing us the privilege of using their speedy bandwidth and then again pay the content provider an increased fee (because they have to buy fast lane access as well to send us the content, and like I said, corporations love their bottom line to keep going up, hence they'll shift any and all additional cost to us).

As far as the FCC's role as a supervisor of honest transactions, don't get your hopes up; usually the terms of these transactions are between companies that like to keep them secret, and FCC can't be everywhere at the same time.

Basically, we're screwed; we either pony up whatever corporations want us to pay to access content at decent speed, or we just move to another country. -

alextheblue ReplySo in other words: we don't care that you already payed for the bandwith dear customer. We will be constrolling your traffic and charging not only you, but also the web services you visit.

Someone has to pay. As streaming traffic increases, and the quality (bandwidth) of the streaming videos continues to increase, networks will be increasingly taxed. Do you honestly think average data usage can spiral up and up (exponentially more customers streaming HD and UHD content) and ISPs won't raise prices? We've really got two choices: ISPs can either raise prices across the board, or negotiate with the content providers responsible for gobbling up all this bandwidth. That in turn will cause those content providers to hike prices (slightly) but this only affects those using said content service(s).

In other words so-called net neutrality is really just more government progressive regulation, designed to pass the pricing burden along to everyone, not just those who use the services in question. I don't know about you, but the free market has done pretty darn well for me so far, in terms of internet access. The bottom line is that the article has it backwards: the internet as we know it exists without net neutrality. -

skit75 "The bottom line is that the article has it backwards: the internet as we know it exists without net neutrality."Reply

When Netflix secures a back-end bandwidth connection as they just did, they pretty much eliminated ever having a direct competitor. What start-up could ever compete with that? That doesn't sound neutral to me. -

Nilo BP Right. Let's give the politicians and bureaucrats more power to regulate the Internet. What could go wrong? It's not like they turn everything under their care into a stiffened lawyer- and lobby-fest. That's such tinfoil-hat thinking. And abuse? Why they would never! The evil corporations are the enemy, I tell you!Reply

Club Benefits

Club Benefits