Tom's Guide Verdict

Detroit: Become Human takes on complex themes about humanity and technology and is visually stunning, but it's too heavy-handed in its storytelling and has lackluster acting.

Pros

- +

Beautiful graphics

- +

Has a message

- +

Replayable

Cons

- -

Bites off more than it can chew

- -

Some mediocre acting

- -

Extra branches don't change much but require repetitive play

Why you can trust Tom's Guide

Detroit: Become Human challenged me not because it had something to say, nor because of the themes it tackled. Instead, it challenged me with how it conveyed its message: a branching story that changes based on a vast array of choices that you make every time you play.

The game, developed by Quantic Dream (led by auteur director David Cage) exclusively for the PlayStation 4, follows three androids in Detroit in the year 2038. Connor (Bryan Dechart, "Jane By Design") is a detective sent by android company CyberLife to investigate "deviant" robots that feel emotions and believe they are alive. Kara (Valorie Curry, "The Tick") is a household servant who takes charge of an abusive father's daughter, and Markus (Jesse Williams, "Grey's Anatomy") starts as a companion robot who finds himself leading a charge to give robots freedom and equal rights.

If those three plots sound like a lot for one game, that's because they are. But this isn't Quantic Dream's first attempt at an ensemble piece with a story that mutates based on player actions. However, this one appears, at least at first, to have far more variance than previous titles from the studio, including Indigo Prophecy, Heavy Rain and Beyond: Two Souls.

MORE: PS4 Games: Our Staff Favorites

In fact, the game branches out so much that it shows off the potential branches after every single chapter in a way that almost fetishizes them. "Look at all these options," it seems to say. "Look what you missed. Don't you want to play me more?"

The Medium Is the Message

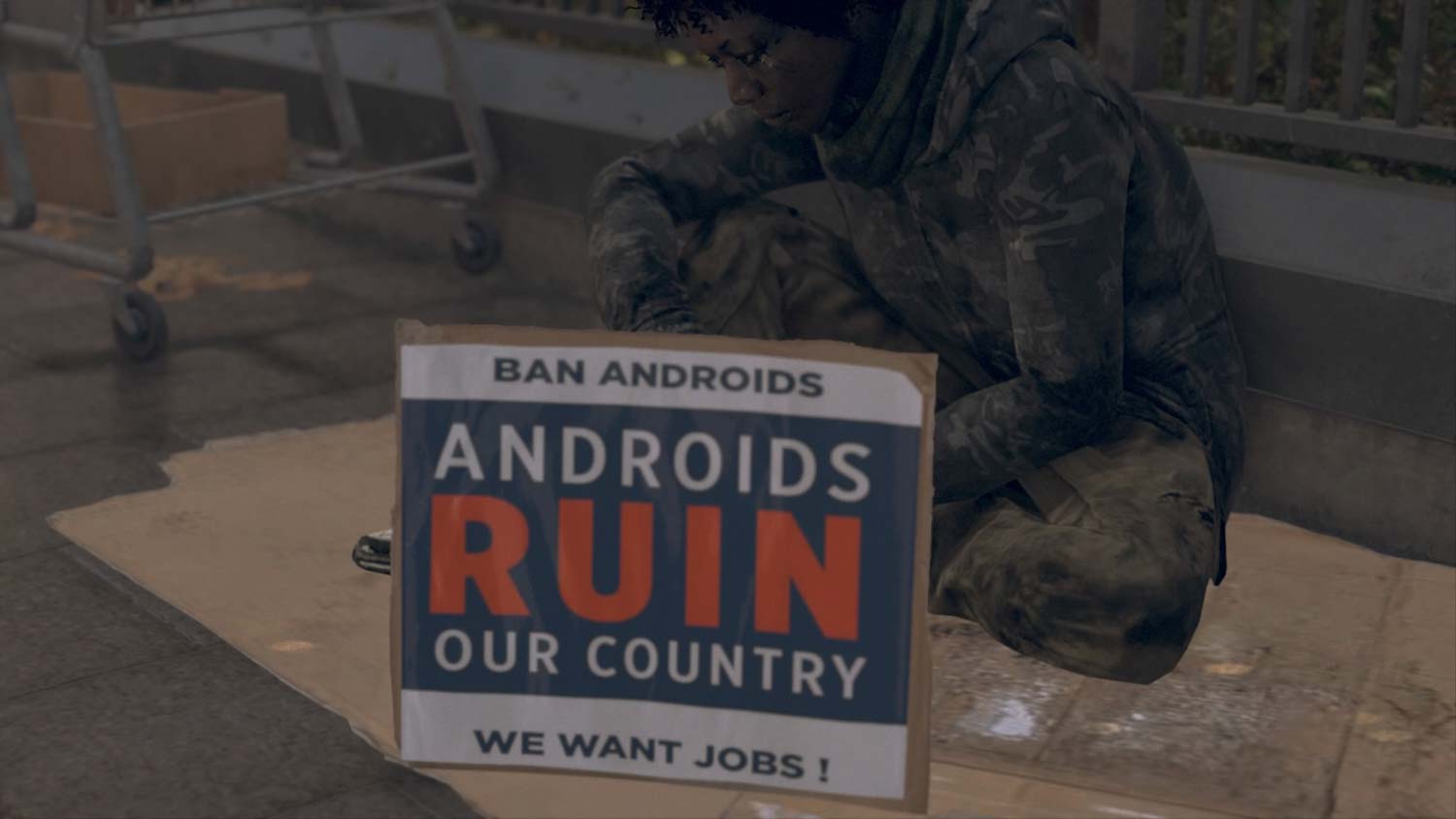

But no matter how you play, the game's themes and narrative are largely the same (though you might miss some story beats if a character dies early on). And Cage and Quantic Dream have a lot to say. Detroit, on its surface, is tackling a near future in which humanity has created technology smarter and more capable than itself, and the game shows how people deal with that. I'd say that Detroit uses androids to tell a parable about immigration and racial discrimination, and there's nothing subtle about it. Unemployed humans hoping for spare change hold signs saying androids took their jobs, while androids have a separate compartment to stand in on the bus as their human masters sit in a section several times as large.

That's not to say that the game shouldn't tackle those themes. But the writing, when treating the moral implications of technology that can double as an intelligent species, tells more than it shows, especially when first setting up the stories.

Get instant access to breaking news, the hottest reviews, great deals and helpful tips.

Warning: I start spilling some minor spoilers here. Scroll below to avoid them.

There are some more-interesting comparisons between the androids and the United States' history of injustices. Specifically, in one midgame plot point, Kara meets up with Rose and her son Adam; these are two African-American humans working to help smuggle deviants across the border to Canada, where the use of androids as workers and household companions is far less common. It's an underground railroad in 2038 for robots escaping their own slavery.

But other themes and injustices get far less care. Kara's story begins in a home with child abuse and domestic violence, and, after that drama happens, the game does not reflect upon it again. It's used only as a catalyst for Kara to take the family daughter, Alice, on the run and begin the escape.

This part took some heat after people saw it in trailers for the game, and Cage was defensive, saying we needed to see it in context. But Quantic Dream doesn't have anything to say about how that abuse affects Kara or Alice, except that it's bad. There's other Android abuse in the game, and this could have been a salient point of discussion for how we treat what we can't control. But the game doesn't attempt that discussion.

Detroit uses androids to tell a parable about immigration and racial discrimination, and there's nothing subtle about it.

It's also notable that Kara's story features far more violence and abuse than those of her male-appearing counterparts, who fight only in action sequences. Additionally, Kara is the only character with any form of aesthetic customization (though at least a midgame sequence in a sex club has something for everyone). On the bright side, the game does have a fairly diverse set of supporting characters.

Connor and Markus' stories are the real meat of the game. While Kara is on the run, those stories drive the action. Connor and a human police partner, Lt. Hank Anderson, have a twisted buddy-cop relationship as they try to solve what's causing android deviancy before the problem becomes widespread. Markus learns how to be a leader and decides whether to be a peaceful protester or a violent rebel, and these plots are core to driving the narrative to its conclusion. (However, Markus, too, gets the studio's heavy-handed storytelling, and at one point is given the opportunity to spray paint, "e have a dream," during a protest.)

But the character also gets more agency than anyone else, quickly becoming a messiah-type. Christ allegory for androids isn't easy, and deciding how to lead, or if one should lead, is difficult. These two characters also feature the more-interesting story beats and more fascinating gameplay, like computing which route is the best way to approach an attack or avoid an obstacle. Kara's sneaking missions seem more passive.

And despite all of the opportunities to branch out, the game still feels linear. The chapters are in the same sequence every playthrough, though some might disappear if a character dies, and at the very end of the game, there are some sequences that do change based on events. The three arcs rarely intersect until the very end of the narrative, and it wasn't often that a choice or observation I made far earlier (a gun Kara saw in a drawer and whether it was used, a character Connor saved coming back to say thank you) had a massive emotional impact.

Despite all of the opportunities to branch out, the game still feels linear.

Only in the back half of Markus' story, when the public is aware of changes to androids and is paying attention, do these choices feel like they have weight beyond who lives or dies. Having public perception affect the campaign for equal android rights is a fascinating twist that plays out both on the streets and on cable news.

Spoilers end here.

My initial playthrough, though, ended suddenly and unsatisfactorily. Yes, I could go back and make changes, and see how those affect the story. But I was puzzled as to which of my many choices had caused the final events to happen. While the entire campaign took me about 8 hours, publisher Sony Interactive Entertainment said the game could take up to 40 hours.

Playing through every little change in the midgame is certainly not worth the effort, as you'll still have to play through more-linear parts, though the multiple endings may offer enough for some players to go back. I did find a few drastic differences to the endings while playing Detroit.

Behind the Scenes

Detroit uses the DualShock 4 controller's unique features more than most titles do. A ton of sound effects come through the controller's speakers, emphasizing certain sounds over others. The light bar is constantly changing to reflect androids' status lights, different investigative modes and other in-game options. And it's one of the very few games that uses the touch strip on the controller, which controls when the characters use tablets and other touch interfaces.

But the game's real-time, spontaneous choices also have some consequences. Detroit uses quick-time events constantly, most intensely during emotional moments.

The game is so cinematic that during some of the biggest fights and grueling moments, I wished I could ease my foot off the gas and take it all in. But I also had to focus during those moments, because while the game raised my heart rate, I still needed to be precise to keep the characters alive.

The game is a visual treat, especially in its set design.

I want to watch, though, because the game looks great. While it supports the PlayStation 4 Pro for better lighting and 4K resolution, the game ran beautifully on my 1080p TV and launch PS4. Character models, especially, look wonderful, except some with longer hair. The main characters definitely appear as if they got a little bit more love than the secondary characters, but not to a fault.

The game is a visual treat, especially in its set design, and while its characters approach the uncanny valley, I found that to be thematically appropriate given the nature of the title.

But while the characters look great, they don't all act great. Quantic Dream used motion capture and real actors, but some of it just falls flat. Dechart's Connor is bland and, ironically, too robotic, even as the detective struggles between following orders and wondering about deviants' points of view. Curry's Kara is sweet and motherly, but the character doesn't get enough to do to reveal if she could offer more.

MORE: Nintendo Switch vs. PS4 vs. Xbox One: Which Console Should You Get?

Only Williams' acting stands out among the main characters, with a mix of uncertainty and confidence as the character becomes a leader. Supporting actors show more range, such as Minka Kelly ("The Roommate," "Friday Night Lights") as North, a rebel fighting alongside Markus, and Clancy Brown ("Thor: Ragnarok," "Mass Effect: Andromeda") as Anderson, the hard-drinking police lieutenant dealing investigating deviants.

Bottom Line

Detroit: Become Human is both fascinating as part of the interactive narrative genre and flawed as a story that tries to shoulder immense themes about humanity (and immigration, race and gender) as well as our responsibility to understand technology and think about the consequences of what we create.

The game is worth a try if only to see how the entire structure of story, interactivity, player choice, graphics and use of the controller are intricately built, but the overall meaning isn't deep enough that you need to fill in every slot on the story tree. There's a message buried in there with plenty to think about and action to keep up the pace, but Quantic Dream didn't construct a story that can truly shoulder the burden of everything. And none of Detroit's lessons make the full impact that they could.

Credit: Tom's Guide

Andrew E. Freedman is an editor at Tom's Hardware focusing on laptops, desktops and gaming as well as keeping up with the latest news. He holds a M.S. in Journalism (Digital Media) from Columbia University. A lover of all things gaming and tech, his previous work has shown up in Kotaku, PCMag, Complex, Tom's Guide and Laptop Mag among others.