The Tech Challenges to Photorealistic Games

Some predict photorealistic video games within a decade, but others say the required ray tracing tech simply won't be possible in that timeframe.

When will video games be photorealistic?

At the Develop games conference this July, Epic Games founder Tim Sweeney made a bold pronouncement: "[Videogames will be] absolutely photorealistic within the next 10 years," he told the audience. In other words, developers will be able to make video games that, even when played in real time, will look indistinguishable from reality.

Sweeney's in a pretty good position to comment: Epic Games makes the Unreal Engine, the underlying system (often called an engine) that powers many modern games, including "Borderlands 2," "Spec Ops: The Line" and the "Mass Effect" series.

MORE: 10 Most Graphically Stunning Games of All Time

But then, so is Henrik Wann Jensen, a researcher at the University of California, San Diego's Computer Graphics Laboratory. Jensen pioneered the technique of subsurface scattering — or simulating how light strikes a semi-translucent object such as glass, water or seashells, and then bounces off of it. Jensen says that it will take longer than 10 years to achieve true photorealism in all types of scenes.

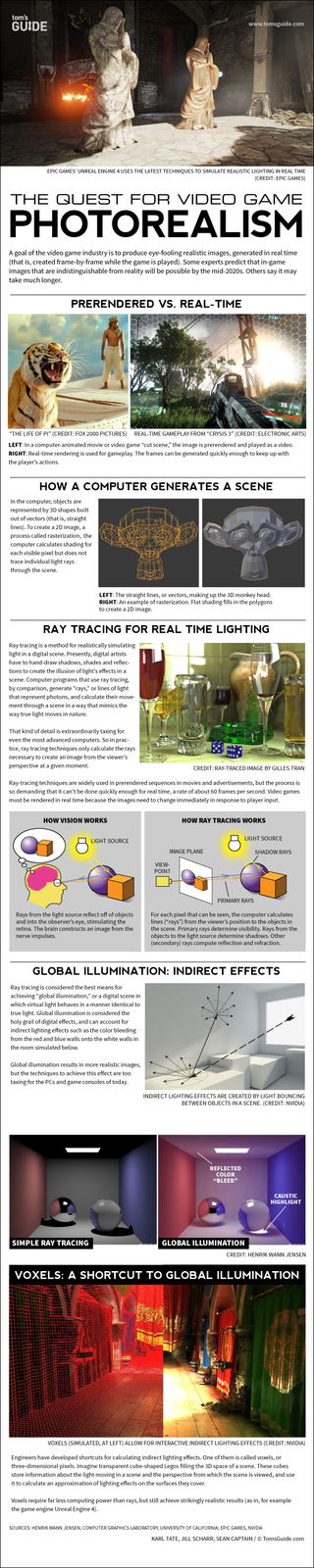

That's because you'd need to produce "global illumination," or a virtual simulation of how light behaves in the real world.

The holy (graphics) grail

Global illumination has been called the holy grail of computer graphics, and a technique called ray tracing is the most reliable and accurate method for achieving it.

Ray tracing is essentially an algorithm that computes the real-time location of millions of light rays as they travel through a virtual scene and reflect off of objects. The algorithm calculates shadows, shades and textures.

Sign up to get the BEST of Tom’s Guide direct to your inbox.

Upgrade your life with a daily dose of the biggest tech news, lifestyle hacks and our curated analysis. Be the first to know about cutting-edge gadgets and the hottest deals.

"If you want photorealism, then there's no way around ray tracing," Jensen told Tom's Guide. "The technology used today is limited, and [3D designers are] running into a wall," he said.

Movies have used ray tracing for years. It's also used frequently in advertising; instead of photographing a product, the advertisers will create a mathematically perfect digital model, and use ray tracing to make the image seem realistic.

In those cases, ray tracing isn't done live; instead, the scenes and images are compiled long before an audience views them. With video games, however, ray tracing has to be done live, which makes the process more difficult.

Real-time ray tracing has also been achieved in various experimental projects, such as Daniel Pohl's ray-traced "Quake 3" demo, but the technique currently requires more processing power than commercial PCs can offer.

Jensen doesn't see that problem going away in 10 years.

Current page: When Will Video Games Be (Truly) Photorealistic? - Tom’s Guide

Next Page Photorealistic Video Games - What Is Photorealism - Tom’s GuideJill Scharr is a creative writer and narrative designer in the videogame industry. She's currently Project Lead Writer at the games studio Harebrained Schemes, and has also worked at Bungie. Prior to that she worked as a Staff Writer for Tom's Guide, covering video games, online security, 3D printing and tech innovation among many subjects.