Fight Like a Girl: The Walking Dead’s Leading Lady

Behind the scenes with Clementine, the zombie-killing, heartbreaking, trailblazing protagonist of 'The Walking Dead: Season Two.'

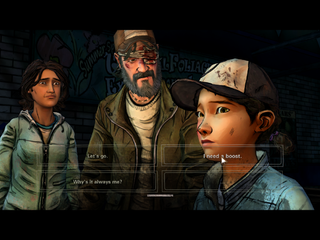

The video game "The Walking Dead Season Two" puts players into a violent zombie-infested world. But there’s a catch: Your player character isn’t a warrior, or even a reasonably able-bodied adult. Instead, players take the role of an 11-year-old black girl from Georgia named Clementine.

Clementine didn’t start out as a leading lady. The first “The Walking Dead” game, released in five “episodes” in 2012 by San Rafael, California-based Telltale Games, starred Lee Everett, a 30-something former history teacher who was on his way to prison for committing murder when the zombie apocalypse broke out.

“The Walking Dead” games are rarely about fighting zombies. Set in the same universe as the comic book of the same name by Robert Kirkman, which also spawned the hit AMC TV show, the video game focuses on Lee’s interactions with the other survivors and his struggle to stay alive without losing his humanity.

Complicating that struggle is Clementine, an orphaned girl whom Lee soon discovers and decides to protect. The player's actions in the 2012 "Walking Dead" set Clementine up to become the protagonist in her own right of "The Walking Dead Season Two."

Clementine’s Origins

“Clem showed up in the first season as this person for Lee to care about, who is obviously external to himself,” Telltale Games Executive Producer Kevin Boyle told us. “Which is much more interesting to me than, ‘How do you be a badass in the zombie apocalypse?’ ‘How do you be a father figure?’ is a much more interesting question.”

Clementine was designed to be something of a parallel with Carl, the son of main character Rick Grimes in the “Walking Dead” comics and TV show. Part of the reason for designing her character as a girl was to create a clear distinction between her and Carl.

But there was more to it than that, Boyle said.

Sign up to get the BEST of Tom’s Guide direct to your inbox.

Upgrade your life with a daily dose of the biggest tech news, lifestyle hacks and our curated analysis. Be the first to know about cutting-edge gadgets and the hottest deals.

“It's not just flipping a switch and saying, ‘Carl’s a boy, and Clem's a girl,’” he said. “There's some differences in how you’re going to present these characters, and how that's going to mean to someone like Lee, and it gave us some interesting space to work in.”

Boyle added that designing Clementine as a girl was not “gender commentary.”

“It definitely didn’t come from a place of saying, ‘We're going to make some commentary on gender by way of “The Walking Dead,”’” Boyle said. “It was more driven by...want[ing] to put someone in the place where they have to make these hard decisions [that] matter to people who are more important than themselves.”

The ‘Daddening’ of video games

“The Walking Dead” wasn’t the first video game to center around an older man and his relationship with a younger character (usually a girl) whom he must protect or save. In 2010, games such as “Silent Hill: Shattered Memories,” “Heavy Rain” and “BioShock 2” led gaming magazine Kotaku’s Stephen Totilo to observe what he dubbed the “Daddening of Videogames.”

The first “Walking Dead” game, centered around Lee’s fatherly relationship to Clementine, came out in 2012. In 2013, the two top contenders for Game of the Year, "BioShock Infinite" and "The Last of Us," had players in the role of middle-aged white men (Booker and Joel) charged with protecting younger women (Elizabeth and Ellie), whom the men saw as daughters.

But these games also did something their predecessors hadn’t: they let players briefly play as the young women. In “The Last of Us,” players took the role of Ellie for a brief section about two-thirds of the way through the game, and again in a sort of epilogue released as downloadable content (DLC) in February 2014. In “BioShock Infinite,” Elizabeth was the player character of the game’s second DLC, “Burial at Sea: Episode 2.”

Those tentative steps led up to the first episode of "The Walking Dead: Season Two," which went live in December 2013 and is the first mainstream game in which the “protected daughter” becomes the player character in her own right.

Putting Clementine in control

Lee’s story ended with Episode Five of the first “Walking Dead,” but the video game’s explosive popularity convinced Telltale Games to do a second. When the team started brainstorming on who would be the new main character, Clementine’s name came up.

“l feel like we knew we wanted to do this, and obviously there was some trepidation about taking gamers and asking them to take the perspective of this eleven-year-old girl." Boyle said. “It's kind of new ground, and we were excited about it, but I'd be lying if I said there was no nervousness about that."

Age was a factor. Even if “The Walking Dead” is more about conversations than combat, playing as a character too short to reach a zombie’s head (the only way it can be killed) would impose a serious restriction on what players could accomplish.

But making Clementine the player character of “Season Two” breaks new ground in other ways too. Among games in which you can’t customize your player character’s appearance, female and black protagonists are still in the vast minority.

Telltale considered many ideas for a Season Two protagonist. Some of those ideas eventually made their way to what would become "400 Days," an expansion of the first "Walking Dead" video game that bridged the gap between “Season One” and “Season Two.” But in the end, Clementine emerged as the clear favorite.

“Carrying through with [Clementine] just had so much more weight for the second season than anything else we might have considered," Boyle told Tom's Guide.

When Telltale announced, several months before Season Two premiered, that Clementine would be the new player character, fan response was “overwhelmingly positive,” according to Job Stauffer, Telltale Games’ director of public relations.

But online, some fans were extremely skeptical of playing as Clementine, even before “Season Two” came out. The writers and designers at Telltale knew they would have to teach players to “be” Clementine instead of merely Clementine’s protector.

"We did put thought into this early…. go[ing] from a player character who’s protecting an NPC [non-playing character] to what we’re doing with ‘Season Two,’" said Mark Darin, a writer and designer on “The Walking Dead.” "We were concerned with what kind of disconnect that was going to be.”

Player as protector

The issue of a female player character being seen as needing protection goes far beyond Clementine in “The Walking Dead.”

Many developers -- and players -- consider playing as a female character a relationship of protection instead of embodiment.

"When people play Lara [Croft, the player character of “Tomb Raider”], they don't really project themselves into the character,” Ron Rosenberg, executive producer of the 2013 “Tomb Raider” reboot, told told Kotaku’s Jason Schreier.

“They're more like 'I want to protect her.' There's this sort of dynamic of 'I'm going to this adventure with her and trying to protect her,’” Rosenberg said. “When you see her have to face these challenges, you start to root for her in a way that you might not root for a male character."

Lara Croft has always been the main character of the long-lived “Tomb Raider” series, and is perhaps the most recognizable female character in video game pop culture. Rosenberg's comments were widely criticized, particularly among female gamers.

Telltale Games’ approach to Clementine is different than Rosenberg’s approach to Lara Croft: Regardless of whether individual players might be inclined to approach a female character as someone to “protect” instead of to “be,” players of “The Walking Dead” already have an established protective instinct over Clementine from Season One.

“The first couple of episodes [of “The Walking Dead: Season Two”] ... were designed to cater to this, [to] allow the player to still have this protective sense over Clementine even though they are playing as Clementine at that point,” Darin said.

However, Telltale also designed the early parts of “Season Two” to teach players to shift toward becoming Clementine.

“We were kind of trying to drive the player [from] these places of protector from an outside standpoint to protector from a more internal perspective,” Darin said.

To do this, the first parts of “Season Two” broke Clementine away from groups. This is why the beginning of “Episode One” saw Clementine separated from Krista and alone in the woods before eventually meeting up with the new group who forms the main supporting cast of “Season Two.”

“You're not feeling that protective nature of other characters on Clementine,” Darin said. “You’re transitioning from that point of wanting to protect her to having to take control to protect her. When she's facing the dog, when she's facing the zombies by herself, all these things she has to do by herself….get you to a place where now you're protecting Clementine as Clementine.”

We are all Clementine

The creators of “The Walking Dead” seem to not want to make statements about Clementine’s race or gender, or what those aspects of her identity may mean, either in the world of “The Walking Dead” or in the current video-game landscape.

For the game’s creators, Clementine’s age is the most defining factor in the way that both players and other characters within the game world treat her.

Yet Clementine cannot count on any special treatment. Her protector, Lee, is dead: now she’s just another survivor struggling to stay alive by any means necessary.

“That's kind of one of the main pillars of the season: Either you have a pulse, or you're a zombie. Every living character is a survivor and that’s all,” Stauffer said.

“Within [“The Walking Dead”] universe, people are certainly no less awful than they were before,” Boyle said. “It's really an opportunity for the worst in people to come out.

“That's one thing that Robert [Kirkman] really pushes on [in the comics], and we've gone in that direction as well,” he added. “These zombies are out there as this perpetual threat over the course of nature, but the real horrors tend to come from people.

“Clementine being a kid, that tends to be the differentiating factor for her versus the rest of the group,” Boyle said. “We don’t really spend a lot of time focusing on her race or even particularly on her gender, although that's obviously a part of who she is.

“As a player, how much of that you want to bring it into the space you’re left to roleplay in is kind of for you,” he said. “We don’t want to make assumptions about what’s driving the decisions you’re making, but we certainly haven't set up the game to make it about race or gender or sex.”

Of course, that doesn’t mean that players can’t roleplay Clementine with a consciousness of her gender, race or any other aspect of her (or the player’s own) identity. Like all video game player characters, Clementine is an avatar -- a projection of the human player.

“I think by not making assumptions about where the player's coming from when they make those choices, it gives you a lot more space to map your own take on the experience of the game,” Boyle said.

Email jscharr@techmedianetwork.com or follow her @JillScharr and Google+. Follow us @TomsGuide, on Facebook and on Google+.

Jill Scharr is a creative writer and narrative designer in the videogame industry. She's currently Project Lead Writer at the games studio Harebrained Schemes, and has also worked at Bungie. Prior to that she worked as a Staff Writer for Tom's Guide, covering video games, online security, 3D printing and tech innovation among many subjects.